Bon nombre de nazis croyaient au principe de la race supérieure venue des régions septentrionales de la planète, là où se trouvait la mythique Thulé. Mais ils croyaient aussi en l'existence de royaumes souterrains, d'une Terre creuse où se serait réfugiée une race de surhommes. Afin de découvrir l'accès à ce monde souterrain qui, depuis le début du 19ème siècle, avait généré une importante littérature, des expéditions avaient été entreprises. L'accès principal était supposé se trouver à la hauteur des pôles.

Du fait que certains dirigeants nazis adhéraient à de telles idées, il n'y aurait rien eu d'étonnant à ce que, après l'expédition navale de à du capitaine Richter, le Reich ait installé une base sur la Terre de la reine Maud qu'il revendiquait. Il semble en tout cas qu'il ait régné là-bas une certaine activité navale et que des combats s'y soient produits au cours de la seconde guerre mondiale.

Au commencement

L'amiral D. C. Ramsey, chef des opérations navales, signe à Washington une série d'ordres adressés aux commandants en chef des Flottes Atlantiques et Pacifiques. Les ordres établissent le Project de Développements Antarctique (Antarctic Developments Project), qui doit être mené durant l'été Antarctique, de à . Le chef des opérations navales, l'amiral Nimitz, donne au projet le nom de code "Opération Highjump".

Les instructions sont pour 12 navires et des milliers d'hommes de faire route vers l'Antarctique pour :

- entraîner le personnel et tester le matériel pour les zones glaciaires ;

- consolider et étendre la souverainté américaine sur la plus grande partie praticable du continent Antarctique ;

- déterminer la faisabilité de l'établissement de bases dans l'Antarctique et de rechercher des sites possibles pour des bases ;

- de développer des techniques pour établir et maintenir des bases aériennes sur la glace, avec une attention particulière à l'applicabilité de ces techniques à des opérations dans les terres intérieures du Groenland, où, il est déclaré, les conditions physiques et climatiques sont semblables à celles de l'Antarctique, et ;

- augmenter la connaissance actuelle des conditions hydrographiques, géographiques, géologiques, météorologiques et électromagnétiques de la région.

Les plans de la tentative sont d'établir une base américaine sur le Plateau Gelé de Ross près de Little America III, lieu de l'expédition de Byrd entre à . Une fois Little America IV établie, une "expansion radiale externe d'exploration aérienne" pourra être entreprise par des avions basés sur des navires opérant le long de la côte Antarctique et par d'autres avions partant de la base terrestre de Little America. Bien que non explicitement indiqué dans les ordres du , un objectif central du projet est la cartographie aérienne de la plus grande partie possible de l'Antarctique, en particulier la côte.

Le , l'amiral Marc A. Mitscher, commandant-en-chef de la Flotte Atlantique, nomme le

capitaine Richard H. Cruzen, qui participa à l'Expédition de Service Antarctique des Etats-Unis avec

Richard Byrd entre et , comme commandant de l'opération Highjump. L'Amiral

Mitscher demande à Cruzen de terminer le projet lorsque les conditions de la glace et de la mer rendent des

recherches plus avancées "non profitables". Il n'est "pas prévu qu'un navire ou avion reste en Antarctique durant les mois

d'hiver". Les propres ordres de Cruzens sont donnés 2 jours plus tard, centrés autour de la construction et de

l'établissement d'une base temporaire sur le Plateau Glacé de Ross en Antarctique

afin d'étendre

la zone explorée

du continent et de tester le matériel en conditions de gel

. Le 20 novembre, seulement

2 semaines après les premiers bateau en mer, Cruzen donne des instructions supplémentaires indiquant les dates de

départ de navire et leurs trajets, l'affectation du personnel et des équipements, etc. De plus, un autre navire est

ajouté à la liste de ceux partant au Sud — the nouveau porte-avion Philippine Sea — avec l'amiral Byrd à

son bord. Celui-ci doit avoir 6 appareils de transport militaire R4D amarrés sur le pont pour être utilisés depuis

la terre à Little America IV. L'amiral Byrd doit amener un R4D à Little America IV et prendre le rôle de commandant

scientifique en chef du projet. Avant la fin des opérations, Byrd doit effectuer un vol au-dessus du Pôle Sud. Bien

que tout ceci fussent les plans et objectifs établis du projet, le but et l'origine du Projet de Développements de

l'Antarctique de

étaient plus complexes.

Depuis début , un monde sans pitié et déchiré par la guerre refletant une paix toujours fragile,

l'Antartique et les régions polaires deviennent à nouveau un centre d'attraction de tous les intérêts humains. En

janvier, Lincoln Ellsworth annonce à la presse son intention de procéder à un exercice de cartographie terrestre et

aérienne en Antartique. Egalement en janvier, le fameux aviateur Eddie Rickenbacker pousse l'exploration américaine

de l'Antartique, comprenant l'utilisation de bombes atomiques pour la recherche de minerai. A la fin de l'automne,

les flottes de pêcheurs de cétacés des Pays-Bas (Willem Barendsz) et de l'Union Soviétique (Slava) œuvrent dans les

eaux de l'Antartique pour la 1ʳᵉ fois (cette 1ʳᵉ opération allemande de pêche de Antarctique est menée dans une

zone entre Bouvet et les Iles Sandwich du Sud. 5 zoologistes accompagnent le voyage pour des recherches sur les

baleines et les oiseaux). En novembre le New York Times titre sur la course de 6 nations vers l'Antarctique déclenchée par

des rapports indiquant des dépôts d'uranium.

L'article indique que les Britanniques mênent la course en

envoyant une expédition secrète

pour occuper la base Est

de Byrd établie en à à

Marguerite Bay sur la péninsule Antarctique.

En fait, les Britanniques sont actifs en Antarctique depuis des années. Après le début de la guerre, quelques navires de commerce allemands, principalement des pirates, naviguèrent dans les eaux Antartiques à la recherche de victimes potentielles. En , le commandant allemand Ernst-Felix Krüder, à board du Pinguin, capture une flotte de pêche norvégienne (les bateaux-usines Ole Wegger et Pelagos, le navire de ravitaillement Solglimt et 11 baleiniers) aux environ de la position 59° Sud, 02°30' Ouest. Le Pinguin est finalement coulé dans le Golfe Persique par le HMS Cornwall le 8 Mai 1941, après avoir capturé 136550 t de cargaison Britannique et alliée. L'Argentine, une nation restée longtemps neutre, saisit l'opportunité de la guerre pour étendre ses revendications territoriales en Antarctique. En à , le commandant Alberto J. Oddera, à bord du Primero de Mayo, visite l'Ile Déception dans les Shetlands du Sud et le 8 février l'Argentine prend formellement possession du secteur entre les longitudes 25° Ouest et 68°34' Ouest, au sud de 60° Sud. La possession des Iles Melchior est déclarée le 20 février et celles des Iles Argentine le 24 février. Le gouvernement argentain avertit officiellement le gouvernement du Royaume-Uni le , leur faisant savoir qu'ils ont laissé des cylindres de cuivre contenant les notices officielles de leurs revendications sur les 3 sites. En , la British Royal Navy lance l'Opération Tabarin (commandée par Keith Allan John Pitt à bord du Fitzroy et Victor Aloysius John Baptist Marchesi à bord du HMS William Scoresby), afin d'établir des stations météorologiques permanentes à Port Lockroy (Base A) et sur l'Ile Déception (Base B). Les cylindres laissés par l'expédition argentine de sont enlevés des 2 sites comme le cylindre laissé aux Iles Melchior. Une occupation est entreprise, sans succès, à Hope Bay et les investigations ne trouveront par la suite aucune base viable sur la Péninsule Antarctique. L'expédition visite également les Iles Orkney du Sud et la Georgie du Sud et durant l'hiver 1944, des programmes de géologie, biologie et de topographie sont menés. C'est la première d'une série d'expédition britanniques de la Royal Navy, de l'Inspection des Dépendances des Iles Falkland, et de l'Inspection Britannique de l'Antarctique.

En le gouvernement des Dépendances des Iles Falkland est établit et en décembre de cette même année des timbres de la poste paraissent pour 4 des dépendances — Graham Land, les Iles du Sud Shetland, la Géorgie du Sud et le Iles Orkney du Sud. Fin , l'Opération Tabarin II commence avec l'aide d'un troisième navire, le Eagle, commandé par Robert Carl Sheppard. Les 2 stations existantes sont réactivées et une nouvelle station météorologique est établie à Hope Bay (Base D). Un refuge est construit à Sandefjord Bay (Base P) sur l'Ile Coronation dans les Iles Orkney du Sud (détruite par la suite par une tempête en ). A la fin de la guerre, les responsabilités administratives des bases établies sous l'Opération Tabarin sont transférées de l'Amirauté au Bureau Colonial sous leur nouveau nom, l'Inspection des Dépendances des Iles Falkland (Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey, ou FIDS). Au cours de l'été Antarctique de à , la FIDS établit de nouvelles bases sur Cape Geddes, l'Ile de Laurie (Base C) et l'Ile Stonington (Base E). L'été suivant, la FIDS établit des sites sur l'Ile Winter dans les Iles Argentines (Base F), sur l'Ile Signy dans les Iles Orkney du Sud (Base H) et un nouveau refuge est construit et temporairement occupé dans la Baie de l'Amirauté, sur l'Ile King George (Base G). Fin , Oslo notifie Washington de la possibilité de réaffirmer ses anciennes revendications de régions de l'Antarctique et la 1ʳᵉ semaine de juillet, George Messersmith, ambassadeur des Etats-Unis à Buenos Aires indique que le gouvernement argentain s'apprête à disputer les droits territoriaux des Britanniques sur les Falklands. Quelques jours plus tard Claude Bowers, à Santiago (Chili), informe le Département d'Etat que le gouvernement chilien est furieux des déclarations définitives des Britanniques.

Ajoutant de l'huile sur le feu, les britanniques diffusent une série de 8 timbres postaux le 1er février 1946,

commémorant leurs déclaration des Dépendances des Iles Falkland. Le nouveau timbre représente une carte de l'Antarctique, outrepassant

complètement les déclarations chiliennes aussi bien que celles de l'Argentine. Pour

la 1ʳᵉ fois dans l'histoire, une crise internationale se trame sur les revendications territoriales des terres

vierges de l'Antarctique. L'état

lamentable de l'économie mondiale porte les plus hautes tensions vers une dimension globale. Les nations les plus

industrialisées d'Europe ont subit une incroyable dévastation durant la guerre et nombre de ces pays considèrent

l'Antarctique comme une solution

à leur problème. Le premier à déposer une revendication légitime peut obtenir abondance de ressources brutes

nécessaires et couteuses. Jusqu'alors la position de l'amérique sur les régions polaires a toujours été qu'elle

devaient être ouverte pour l'exploration et la recherche par l'ensemble des parties concernées mais au matin de

l'annonce formelle de l'amiral Byrd de l'Opération Highjump le , les gouvernements

latino-américains deviennent nerveux et suspicieux à propos du célèbre Yankee américain. L'Opération Highjump est

perçue comme une énorme menace pour les future revendications latino-américaines. Après tout, 13 navires et 4700

hommes semblent bien confirmer le fait que les Etats-Unis ont leur propre plan pour partitionner les énormes

portions du continent. L'annonce à la presse officielle de Byrd semble confirmer leur anxiété, Highjump y étant

justifée comme une extension

de la politique de la Marine des Etats-Unis de développement de la capacité

des forces navales à opérer dans n'importe quelles et toutes conditions climatiques.

Un objectif déclaré

publiquement est de consolider et développer les résultats de l'Expédition de Service Antarctique des Etats-Unis de

à .

A ce moment, les suspicions latines semblent justifiées. L'approbation initiale de

l'Opération Highjump est apparemment obtenue lors d'une réunion du Comité des Trois

(le Secrétaire d'Etat, le

Ministre de la Guerre et le Ministre de la Marine) le . Un mémorandum préparé pour la réunion

indique que la Navy propose d'envoyer une expédition en Antarctique dès

. Les objectifs de cette expédition incluent l'entraînement du personnel et le test des

matériels, la consolidation et le développement de la souveraineté des Etats-Unis sur les régions Antartiques, la

recherche de sites possibles de bases et le développement de la connaissance scientifique en général. L'amiral R.

E. Byrd sera désigné comme Officier-en-Charge du projet. Pe commandant de la Force d'Expédition sera le capitaine

R. H. Cruzen commandant actuellement l'Opération Nanook, une expédition en Arctique.

Une semaine après la

réunion, Edward G. Trueblood, sénateur directeur du bureau Latino-Américain du Département d'Etat, envoie un

mémorandum au chef du bureau Européen indiquant qu'il n'y a aucune objection à l'Expédition Byrd

tant que

aucun territoire revendiqué par certains gouvernements latino-américains. Le , le Secrétaire

d'Etat exécutif Dean Acheson donne l'accord de son département à Highjump avec l'indication que au regard des

revendications territoriales d'autres gouvernements dans l'Antarctique, il est suggéré

que les régions à visiter par l'expédition navale proposée soient discutée informellement entre les Départements

d'Etat et de la Navy...

Cette discussion est tenue le 25 novembre, seulement une semaine avec le départ des

premiers navires. Acheson écrit au Secrétaire de la Navy James Forrestal le et lui fait part

de son accord total

avec l'avis majoritaire obtenu à la réunion de novembre et que ce gouvernment devrait

suivre une politique définie d'exploration et d'utilisation des zones Antarctiques considérées

désirables pour être acquises par les Etats-Unis.

La position formelle des Etats-Unis étant de ne reconnaître

aucune revendication de territoire en Antarctique,

du point de vue de ce Département les navires, avions ou le personnel du Projet Naval de Développements Antarctiques de

ne sont pas dépendants de droits ou revendications territoriales préalables d'autres états pour

pénétrer et engager des activités de plein droit dans chacune de ces régions ou de procéder à des déclarations

symboliques à cet endroit ou sur des territoires nouvellement découverts pour les Etats-Unis.

L'amiral Marc

Mitscher, commandant en chef de la Flotte Atlantique, est même plus défiant encore dans ses Instructions pour

l'Opération Highjump

fournies le 15 octobre. Les Objectifs

incluent la Consolidation et l'étente de

la souveraineté des Etats-Unis sur la région praticable la plus vaste du contient Antarctique.

Peut-être

les Départements d'Etats et de la Navy souhaitaient des revendictions de territoires supérieures, mais le fait est

qu'aucune déclaration formelle ne fut faite pas les hommes de l'Opération Highjump. Celle-ci ne fut pas lancée en

précipitation pour les ressources naturelles de l'Antarctique ni pour l'objectif principal d'expansion territoriale. D'après les

informations de la conférence de presse de l'amiral Byrd du 12 novembre annonçant l'Opération Highjump, La Navy

dément catégoriquement les rapports indiquant que le voyage sera avant tout une étape dans la course à l'uranium.

'Lors de la première discussion concernant cette expédition, l'uranium ne fut même pas mentionné. Dire qu'il

s'agit d'une course à l'uranium pour l'énergie atomique n'est pas correct', a déclaré l'amiral Byrd.

Cependant, les objectifs de base ne sont pas diplomatiques, scientifiques ou économiques — ils sont militaires.

L'Opération Highjump est, et reste à ce jour, la plus grande expédition Antarctique jamais organisée.

Pré-Highjump : Opérations navales 1945-1946

Les commentaires de l'amiral Byrd dans son communiqué à la presse du indiquent que ...les

objectifs de l'opération sont principalement de nature militaire, c'est-à-dire d'entraîner le personnel naval et de

tester les navires, avions et l'équipement en conditions de régions gelées... Un objectif primordial de l'expédition

est d'apprendre comment l'équipement standard et de tous les jours de la Navy se comportera dans les conditions de

tous les jours

. Les soviétiques s'intéressent de près à ce projet et en font un édito dans leur journal naval,

Flotte Rouge, indiquant à la suite de la conférence de presse de Byrd que les mesures U.S. en Antarctique confirment que les

cercles militaires américains cherchent à soumettre les régions s1[polaires] à leur

contrôle et à créer des bases permanentes pour leurs forces armées.

Les relations sovétiques-américaines se détériorent rapidement au cours de et avec l'intérêt croissant des américains pour les 2 régions polaires, l'anxiété des russes augmente de jour en jour. Les soviétiques réalisent vite que si une 3ᵉ guerre mondiale intervenait entre la Russie et l'Ouest, un champ de bataille stratégique serait très sûrement dans la région polaire du Nord. Il est du plus grand intérêt pour les américains d'exposer et de préparer leurs hommes, navires et équipement aux conditions extrêmes des régions polaires aussi rapidement et efficacement que possible.

L'environnement politique américain de joue également un rôle non négligeable dans l'Opération Highjump. Après la fin de la 2nde guerre mondiale, de nombreux politiques débattent dans le pays à propos du mérite d'un seul commandement militaire unifié sous un seul département de la défense nationale. Au début la Navy agrée à l'idée. Pourtant, au fur et à mesure que les détails arrivent, survient la peur d'une Navy dominée par les jeunes généraux arrogants et rugueux de l'Air Force qui relègueraient la Navy à de simples procédures de défense de la côte. On dit à Washington que les corps de la marine opéreraient sous l'armée alors que les transporteurs aériens seraient sous la direction de l'Air Force. La consolidation économiserait à l'évidence beaucoup d'argent au contribuable américain mais la Navy ne veut tout simplement pas en faire partie. En conséquence, la Navy perd une grande part du soutien populaire. Mi-, les amiraux cherchent un moyen de dramatiser l'efficacité de la marine. Cette anxiété, couplée à la montée de la guerre froide, crée l'opportunité d'une expansion très forte vers l'exploration polaire.

Le 1er programme naval d'exploration polaire est l'Opération Frostbite

(Morsure du froid) à la fin et

pendant l'hiver à . Une poignée de navires accompagnent le nouveau transporteur aérien Midway à

Davis Straits, près des côtes du Greenland, où des hommes et l'équipement subissent un test éprouvant. Déchirés

par les hautes mers et les blizzards féroces dans un froid extrême avec des monceaux de neige sur le pont d'envol,

ils opèrent dans les conditions les plus exigentes pour prouver que de telles opérations sont faisables.

Cependant, l'Opération Frostbite n'a pas été menée assez loin vers le nord. Les été Arctiques sont simplement trop

doux pour exposer inadéquatement et entraîner des hommes à des températures sous zéro. En conséquence, afin

d'entraîner une assez grande marine aux expéditions polaires, le test doit se dérouler dans des régions d'un climat

plus sévère pour une période de temps prolongée.

Le , Le Congrès approuve la Loi Publique 296 demandant au chef du Bureau Climatologique des

Etats-Unis d'établir un réseau international de rapport météorologique dans les régions Arctiques de l'hémisphère

occidental.

Le Bureau Climatologique se tourne vers l'armée et la marine et ensemble, les 3 agences arrivent à

un plan de construction de stations de rapport à Thule (Greenland) et à la pointe Sud de l'Ile de Melville dans

l'Arctique Canadien. Le commandant de la Flotte Atlantique U.S., l'amiral Marc A. Mitscher, sélectionne quelques

navires, désignés sous le nom de Task Force 68, et nomme le capitaine Richard Cruzen commandant de l'Opération

Nanook.

Les premiers ordres de l'amiral Cruzen, donnés le 31 Mai 1946, demandent un plan général dont la 2nde

phase consiste en opérations pour établir des stations d'observation et de rapport du Bureau Climatique U.S.

dans l'Arctique Canadien et le Greenland. De plus, Cruzen commande un brise-glaces, le Eastwind, ainsi

qu'un hydrabion, le Norton Sound, pour opérer aux environs de la limite Sud de la zone de glaces devant

être rencontrée dans la région de Baffin Bay.

Ceci peut être un projet pacifique pour effectuer des

observations météorologiques dans l'Arctique, mais un argument intéressant peut évoquer que ces stations peuvent

être également utilisées comme sites de collecte de renseignements. Quoi qu'il en soit, c'est avec ces 2 projets que

l'U.S. Navy commence son effort pour exposer systématiquement hommes et machines aux rigueurs de la vie polaire.

La "famille" Byrd et Highjump

Mais quel rôle Byrd et ses compagnons, en particulier Paul Siple, jouent durant cette période ? En fait, ils

trouvent la plupart de leur travail de recherche assuré par le gouvernement, le tout au nom de la Défense Nationale.

Paul Siple n'a pas seulement affecté des hommes à des travaux en Alaska et dans le Greenland au cours de la 2nde

guerre mondiale ; il a aussi voyagé en Europe pour conseiller Eisenhower

et ses généraux sur la meilleure manière d'éviter une épidémie de pieds amputés parmi ses hommes. Au printemps

, Siple se rend aux Philippines pour conseiller MacArthur

sur l'habillage et la protection en hiver des forces se préparant à envahir les principales îles du Japon.

Après la fin de la guerre, Siple se retrouve à travailler pour le service fédéral en tant que scientifique civil

pour le Bureau de Recherche et Développement du commandant en chef de l'armée. Il est un homme brillant et pourrait

facilement enseigner à l'université dans son propre département de science et de géographie, mais peu d'universités

contiennent de tels départements et aucun fond n'est disponible pour établir son propre centre de recherche,

particulièrement pour quelque chose d'aussi exotique que l'étude de zones polaires. A la place, il devient un

participant actif de la guerre froide. Il écrira plus tard, Ma nouvelle carrière consistait à introduire

l'application de mes concepts de recherche environnementale à l'équipement et au personnel de l'Armée dans tout

environnement où ils puissent être appelés à combattre pour préserver la liberté de vie. Mon intérêt était de

m'étendre sur des aspects entiers de la recherche basique et le segment dont j'étais un représentant scientifique

finit par se développer dans le Bureau de Recherche de l'Armée.

Mais pas une personne n'est plus responsable de l'Opération Highjump que Richard E. Byrd. La réputation de Byrd a florit durant la guerre. Il a été nommé adjoint spécial du directeur des opérations navales, l'amiral Ernest J. King, et est un ami proche et personnel du président Roosevelt. Entre à il se rend sur les fronts de la guerre en Europe, en Alaska et dans le Pacifique Nord. Mais le fougueux amiral de la vague Antarctique de n'a jamais commandé le moindre navire de combat au cours de la guerre. Maintenant, avec la fin de la guerre, la marine découvre tout à coup qu'elle a besoin de Richard Byrd. Si elle ne veut pas être déchargée de son rôle, en particulier celui de l'aviation navale, un plan pour mettre en évidence sa valeur doit être rapidement élaboré. D'après Paul Siple, c'est Byrd qui persuade le Secrétaire de la Navy James Forrestal et le Directeur des Opérations Navales Chester Nimitz de lancer une énorme expédition navale en Antarctique. A côté de cela, l'obsession de Forrestal pour la menace soviétique trouve une sympathie et un support grandissants au Capitol. Un autre allié proche fut le frère de Richard Byrd, le sénateur Harry Flood Byrd, alors chef de la puissance machine familiale qui a soutenu le parti Démocrate en Virginie. Harry est une figure-clé des Démocrates du "Sud Solide" des années et . Harry possède une grande influence sur la chambre des députés et de nombreux présidents, en particulier les nouveaux présidents à la popularité vascillante, le suivent. Comme on peut s'y attendre, Harry suit Richard quoi que veuille Richard et en , Richard veut retourner en Antarctique. Comment le haut commandement de la marine réussit à convaincre le Congrès de financer l'expédition coûteuse reste un mystère. La Navy n'a pas été responsable d'une expédition au Pôle Sud depuis l'exploration de Charles Wilkes une centaine d'années plus tôt. On peut juste supposer que le pays était excité à l'idée d'engager la plus grande expédition en Antarctique de l'histoire, en temps de paix, dans une aventure n'impliquant apparemment ni morts ni destructions. La "menace soviétique", accompagnée de la menace d'une guerre en Arctique, est peut-être la seule raison.

L'U.S. Navy insiste sur le fait que l'Opération Highjump va être un show naval, avec les intérêts de la marine

prédominant sur les études scientifiques. Les ordres préliminaires de l'amiral Ramsey le

indiquent que Le Directeur de Opérations Navales seul s'entretiendra avec d'autres agences du gouvernement

liées à Highjump. Aucune négociation diplomatique n'est requise. Aucun observateur étranger ne sera accepté.

Il semble donc qu'il y ait peu de place pour les scientifiques et observateurs civils. Par la suite, le directeur

des opérations navales fait part via un courrier à divers autres départements et agences gouvernementaux d'une

invitation à participer modestement à Highjump. D'après le Rapprt des Observateurs de l'Armée, Le Département de

la Guerre répondit promptement à l'invitation de la Navy à envoyer des observateurs sur cette importante

expédition et accrut sa représentation jusqu'à 16, 10 de plus que préalablement alloué par la Navy. Le personnel

comprenait 4 hommes ayant déjà servi en Antarctique

,

dont Paul Siple. Sont également invités à participer des observateurs de l'armée, du Bureau Climatologique, de

l'Inspection Géologique des Côtes, de l'Inspection Géologique et le Service de la Vie Marine et Sauvage. Les études

scientifiques recommandées sont les mesures aérologiques (observations synoptiques, météorologie radar, intensité de la radiation solaire), les

observations magnétiques terrestres, les études géologiques aériennes (y compris la Recherche Aérienne pour les

Matériaux Source d'Energie Atomique

), l'étude des rayons cosmiques, etc. Des scientifiques et chercheurs

réputés présents sont Jack Hough, Bill Metcalf et David Barnes de l'Institut Océanographique de Woods Hole. Dès le

retour des navires de l'Opération Nanook, le 18 september, le planning est intenfié et une date de départ officielle

est annoncée pour le 2 décembre.

Les plans finaux

A l'exception de Cruzen, tous les navires et hommes prévus finissent par être changés. Le chef de l'expédition est Richard Byrd, qui base ses opérations à Little America et tentera plus tard de voler jusqu'au Pôle Sud, et peut-être au-delà. Afin d'exposer autant d'hommes que possible aux conditions polaires, aucun des navires de l'Opération Nanook n'est envoyé au Sud. A la place, les commandants des Flottes Pacifiques et Atlantiques désignent chacun 6 vaisseaux pour l'expédition. Le drapeau de l'expédition, Le Mont Olympe, vient de la Flotte Atlantique. Le navire est bourré d'équipement de communication et électronique relativement primitif pour l'époque. Viennent aussi de la Flotte Atlantique le brise-glaces Northwind, l'hydravion Pine Island, le fleet oiler Canisteo, le destroyer Brownson, le sous-marin Sennet et, dernier à partir pour arriver au même moment en Antarctique, le nouveau transporteur de flotte aérien Philippine Sea. La Flotte Pacifique fournit le destroyer Henderson, les vaisseaux-cargo Yancey et Merrick, l'hydravion Currituck, le fleet oiler Cacapon et le brise-glace de la marine Burton Island.

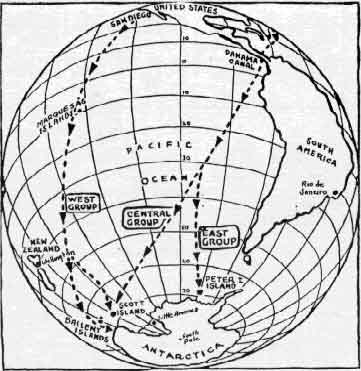

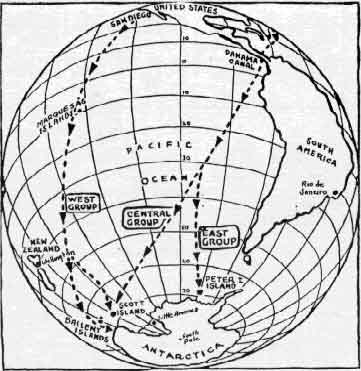

Une conférence se tient au début de l'automne au Bureau Hydrographique Nael à Suitland (Maryland), pour préparer les cartes et les directives de navigation de l'Opération Highjump. Ils réalisent rapidement que les cartes les plus sûres de la Mer de Ross sont celles de l'amirauté britannique. Des copies sont envoyées à tous les navires. Cruzen, Byrd et d'autres réfléchissent sérieusement aux objectifs et priorités de l'expédition et concluent ensemble que le seul et plus spectaculaire objectif doit être la cartographie aérienne de la côte Antarctique ainsi que ses terres intérieures tant que possible. L'expédition se divisera en 3 groupes dont le Groupe Central, mené par le sous-marin Garde-Côtes Cutter Northwind, poussant jusqu'au bloc de glace de la Mer de Ross. Suivent de près derrière les navires-cargos Yancey et Merrick, le sous-marin Sennet (envoyé pour tester ses capacités opérationnelles en conditions polaires) et le porte-drapeau Mont Olympus (le nouveau-brise-glaces de la marine Burton Island, membre du Groupe Central, effectue toujours des entraînements de base et des tests en mer au large des côtes californiennes lorsque l'Opération Highjump est lancée).

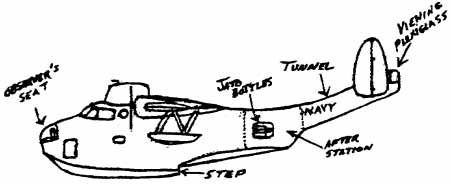

Les cartes et directives de navigation utilisées pour l'Opération Highjump furent assemblées comme une collection d'esprits au Bureau Hydrographic de Suitland (Maryland), au début de l'hiver . Les cartes de la Mer de Ross préparées par l'Amirauté Britannique semblent être les plus fiables et sont par la suite reproduites et distribuées à l'ensemble des navires. En conséquence, le Northwind allait reposer exclusivement sur ces cartes pour guider les navires du Groupe Central au travers de la zone de glace et dans la Mer de Ross. Les amiraux Byrd et Cruzen (promus contre-amiraux avant leur départ) déterminent que la plus grande priorité de l'expédition doit être la cartographie presque exhaustive de la calotte Antartique et aussi vers l'intérieur que possibleL'expédition doit être divisée en 3 groupes. Le Groupe Central, mené par le Northwind, incluerait les navires cargo Yancey et Merrick, le sous-marin Sennet (envoyé spécifiquement pour tester ses capacités en conditions polaires) et le navire porte-drapeau de l'expédition, le Mont Olympe. Le brise-glace Burton de la Navy arriverait plus tard pour les étapes finales de Highjump. Once alongside the shelf ice at the Bay of Whales, Little America IV would be established. A landing strip for the six R4D (military version of the DC-3) transport planes would be laid out, serving as a base of operations for the aerial mapping missions to follow. In order to carry out this mission, the Central Group would be supported by the aircraft carrier Philippine Sea which would carry the planes, along with Admiral Byrd, to the edge of the ice pack. From here the planes would make the risky six-hour flight to Little America IV. To assist the planes in takeoff from the narrow flight deck, Jet-Assisted Take-Off (JATO) bottles, filled with jet fuel, would be attached under the wings and ignited just seconds after the plane began to roll, thereby dramatically increasing the speed necessary for take-off. The R4D's were the heaviest aircraft ever to launch from a carrier. They would also be the first to take off on one end with wheels and land on the other end with skis. They had only 400 feet of take-off to work with, otherwise their wide wingspan would collide with the carrier's superstructure. First to depart would be Admiral Byrd, with skilled polar flyer William "Trigger" Hawkes at the controls.

On either side of the Central Group and the Phillipine Sea would be the Eastern and Western Groups. The Eastern Group, built around the seaplane tender Pine Island, would rendezvous at Peter I Island and from there would move toward zero degrees longitude (Greenwich Meridian). Joining the Pine Island would be the oiler Canisteo and the destroyer Brownson. The Western Group would be built around the seaplane tender Currituck. The Currituck would rendezvous, together with the oiler Cacapon and destroyer Henderson, at the Balleny Islands and then proceed on a westward course around Antarctica until, hopefully, it met up with the Eastern Group. Each of the seaplane tenders would be supplied with three Martin Mariner PBM flying boats, the largest and most modern seaplanes built during World War II. Plans were made to daily lower each plane into the sea, from where they would take off on flights of many hours in an attempt to photograph as much of the coast and interior as possible.

If all went according to plan, and the crews performed flawlessly, then there was a chance, as Admiral Byrd later wrote, "that a complete circle could be closed around the continent. It was hoped that in a few weeks more would be learned of the great unknown than had come from a century of previous exploration by land and sea".

Throughout à , swift preparations were underway around the country. Admiral Cruzen and his subordinates on both coasts were busy ordering parkas, goggles, boots, thermal underwear, special tents and the matting for Little America's new runway. Special trainers were sent by Byrd and Paul Siple into the New Hampshire woods to work with the dogs. Meanwhile, caterpillar tractors, forklift trucks, "weasels" (powered sleds) and other heavy machinery were being manufactured and loaded onto railroad cars and shipped to docksides in California and Virginia. But all was not well. Huge concerns were in the minds of planners as, for the very first time in Antarctic history, every vessel used in the expedition would be steel hulled. Steel is certainly stronger than wood, however wood tends to splinter in the viselike grip of pack ice while steel is usually ripped apart. It is true that Byrd successfully maneuvered the Eleanor Bolling through the ice pack and around the shelf in , however the Bolling's hull was significantly thicker than that of most of the ships used in Highjump. Compounding this problem was the fact that all but a handful of men were totally lacking in adequate training for polar conditions. As Professor Bertrand later noted, "Although personnel of Operation Nanook served as a nucleus for staffing Operation Highjump, the much greater size of the later expedition necessitated the filling of many posts with men who had no previous polar exploration. It was possible to obtain the services of only eleven veterans of previous U.S. Antarctic expeditions. Only two pilots in the Central Group of the Task Force had experience in flying photographic missions". As a matter of fact, none of the seaplane pilots or flight crews had ever flown in Antarctica before. Only Byrd's personal pilot, Commander William M. Hawkes, had polar experience as he had logged hundreds of hours in the treacherous skies of Alaska. Extensive ship movements only made matters worse as the lives of many men and their families were suddenly disrupted, uprooted and shipped across country on the eve of the expedition. The Merrick and Yancey were attached to the Atlantic Fleet when in October they were ordered to sail for Port Hueneme, California, to prepare for the exercise. The Mount Olympus, which played a major combat role in the war, and the Pine Island had spent most of their lives in the Pacific Fleet and now were suddenly ordered to the Atlantic Fleet for preparations. With all the turmoil, Captain Rees of the Mount Olympus wrote in exasperation to Admiral Cruzen, "Details as to the nature of the operation are completely unknown. It is therefore urgently requested that this vessel be informed at once as to what special equipment, instruments, clothing, etc. . . the ship must obtain in the limited time remaining. The ship can not be considered a smart ship". The carrier Philippine Sea had completed its shakedown cruise only weeks before, yet now the ship and its crew were expected to launch the largest planes ever sent from a carrier deck, quite possibly under extreme weather conditions. The navy's new icebreaker, the Burton Island, was still undergoing basic sea trials and training off the California coast as Operation Highjump began. This meant that during the earliest and possibly most crucial stages of the expedition, Cruzen and his untrained men would have to rely solely on the Northwind to get the four thin-skinned ships of the Central Group through the ice pack and into the Ross Sea. Not only that, but if any of the ships from the Eastern or Western Groups ran into trouble, only the Northwind would be able to assist. If the Northwind should become disabled herself, the entire Central Group could be left helplessly for weeks, deep in the Ross Sea, certain prey for icebergs and the crushing pack ice.

The inexperience of the men, particularly the fliers, was all too apparent. One of the pilots, Lieutenant (jg) William Kearns, later recalled that volunteer pilots, navigators and air crewmen were gleaned from both the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets "in the fond hope that some experienced men would be among those selected. Since the vast majority of personnel knew nothing about the type of operation for which we were destined, we were forced to dig into books for even the most elementary information". The information was frightening. Temperatures were far colder than the Arctic regions and the fliers could fall prey to an empty, inhuman landscape from which no help could be expected. Traditional navigational aids were of little help as Mercator projections were of no use due to the convergence of meridians at high latitudes and the consequent distortion of areas between the parallels. Thus, a grid system would have to be used. "From the experiences of men who had been to both regions and learned the hard way, we saw that polar flying, even at its best, was never really safe. There were no airways, no weather reporting stations, no convenient alternate airports. We were, in fact, extremely fortunate if we found any charts at all available for the 'Highjump' operating area. With all these facts in mind, some of us began to regret our decisions to become intrepid Antarctic explorers, and to long for the good green lands and the waving palms of Florida". Pilot Thomas R. Henry wrote, "Once a plane rose from the ski strip at Little America, it was virtually imprisoned in the sky for at least five hours; it could come down only with a crash landing on the rough ice surface, which would almost certainly ruin the aircraft itself and seriously endanger the crew". If the mapping objectives of Highjump were to be met, planes would have to be heavily overloaded with photographic equipment and topped-off fuel tanks. Antarctica was simply too large, its weather too unpredictable, not to make every flight fully count in terms of photographic exploration during the brief expedition.

A certain sense of uneasiness flowed through the seaplane crews at Norfolk, Virginia. The follow-up report on their mission stated that the operation "was characterized by a very limited period of personnel training, material inspections and logistic planning". The crews of all six PBM's were drawn from current squadrons and assembled at the Naval Air Station, Norfolk, VA, on . This gave them only one month to prepare. Meanwhile, the PBM's were winterized and fitted out with some special navigational instruments, as well as the trimetrogon photographic equipment. Survival gear was gathered as the crews were quickly instructed in polar navigation. On November 27 three of the seaplanes flew from Norfolk to San Diego, California, and were lifted aboard the Currituck, which was in its final loading phase. Back in Virginia, the other three planes were brought aboard the Pine Island. When the Pine Island reached the Panama Canal, the planes had to be sent off, later landing at Balboa on the Pacific side, in order to get through the canal.

Despite the many risks of such an adventure, morale actually turned for the better as sailing time approached. Married men, many of whom had spent prolonged months of separation from their spouses during the war, were obviously less enthusiastic than their generally younger, unmarried peers. But, as the official report noted, the general mood was one of a "trip of a lifetime" and of "a big expedition to Antarctica".

As last-minute preparations were underway, diplomats of several nations continued to snip at one another. On November 13, Ellis O. Briggs of the Latin American bureau of the State Department noted that "The [British] Empire continues to bleed over the forthcoming Byrd Antarctic expedition if Mr. Everson of the British Embassy who called on me this morning is to be believed". Briggs told Everson "that our Government is at least as interested in practicing cold water operations as it is in what may be found sub-zero, sub-rosa, sub-ice caps, etc." However, Everson "did not seem altogether soothed". Briggs went on to say that Everson muttered something about Antarctica being British territory and that the United States should have cleared the expedition with His Majesty's government. "If London has any such notions as that, I assume steps will be taken to disabuse our British friends of any belief that we consider Antarctica British", Briggs concluded. Two days later Briggs noted that New Zealand, Australia and Chile had also indicated a rather keen interest in the motives and objectives of Operation Highjump. Would the United States abandon current policy and lay claim to vast areas not only claimed by the above, but also by the French, Norwegians and Argentineans? Briggs noted that representatives of the governments of Australia, New Zealand and Chile requested permission to go along as observers but that permission was firmly opposed by the navy. Finally, on November 27 as the Yancey and Merrick began to cram aboard every last item remaining on the docks at Port Hueneme, Acting Secretary of State Dean Acheson telephoned Briggs to ask if he foresaw any "political difficulties" in the "Byrd expedition". According to the Secretary, President Truman's naval aide, Admiral Leahy, had expressed concern that it might be too bad to have the Chileans, "now so full of good will, acquire hurt feelings". Briggs attempted to put his President at ease, saying that both Chile and Argentina had expressed "some interest" in Highjump, however "I did not believe that relations with either country would be affected in any substantial or noticeable way by the expedition". Perhaps Secretary Acheson was put at ease, but the same can not be said of the President. At the very last moment, probably December 1 or 2, President Harry Truman tried to stop Operation Highjump. Briggs was told that "the navy" had suddenly been called into the Oval Office and told to cancel the expedition. When "the Navy Department remonstrated, pointing out that if the expedition did not sail now the opportunity would be lost, the President is supposed to have relented and allowed the expedition to proceed". Who the President addressed that day is unclear, but it was possibly Nimitz, or more probably James Forrestal. In any event, neither Byrd, Cruzen or the thousands of other men under their command were aware of how close they had come to missing their "trip of a lifetime". By December 3, 1946, most of the ships were at sea; all the rest, but for the Burton Island, were about to depart. Operation Highjump was underway.

L'expédition commence

Le 1er navire à quitter son port d'attache est le brise-glace Northwind, partant du port de la Marine de Boston le . Le il arrive à Norfolk, VA, rejoignant le navire Mount Olympus, le transporteur d'hydravion Pine Island et le destroyer Brownson pour les préparatifs finaux. Finalement, le , tout est prêt. Peu avant , Byrd arrive à bord du Mount Olympus pour un déjeuner final avec Dick Cruzen. Afterwards, Byrd accoste et annonce qu'il va attendre pour naviguer sur le transporteur Philippine Sea 30 jours plus tard. Il nomme Paul Siple pour être son représentant en chef au Département de la Guerre sur l'expédition and with that, the Pine Island cast off, to be followed shortly thereafter by the other three ships. The tiny fleet moved down the Roads, past Old Point Comfort, Cape Henry and finally into the open sea where they abruptly turned south for their 10000-mile voyage to Antarctica. Le also found the ships of the Pacific Fleet pulling away from various California ports: the seaplane tender Currituck and destroyer Henderson from San Diego, the oiler Cacapon from San Pedro and the cargo ship Yancey from Port Hueneme. The cargo ship Merrick was still busy loading gear and would pull out of Port Hueneme on December 5. The Atlantic Fleet sailed around Cuba through the Windward Passage and across the Caribbean to Panama. On December 7, the four ships passed through the canal, docking at Balboa on the Pacific side. Waiting for them was the submarine Sennet and oiler Canisteo, since they had previously been assigned to the Central American station. By December 10 all the ships had arrived and as they left Panama behind, the ships fanned our over many hundreds of miles as they made their voyage south.

Opérations en Antarctique

Les activités du Groupe Central

The Central Group rendezvoused at Scott Island on , in order to follow the Northwind through the pack ice into the open waters of the Ross Sea. The modern icebreaker is one of the most distinctive and remarkable vessels ever designed. And from this distinctive group of ships came the hardest working vessels of their kind: the Wind-class sisters built during and just after World War II. A total of seven were built by the Western Pipe and Steel Company of San Pedro, California. However, four of them were sailing with a Soviet flag in as part of the lend-lease program with the Soviets, and the last ship was not returned until . (When the American crew arrived at Bremerhaven to take over the ship, subsequently renamed Staten Island, it was in horrific condition. The ship's desk drawers were crammed with rotting tins of fish and the flight deck area was smeared with chicken blood and feathers. It would take two cruises to the Arctic before the stench would disappear). Of the three remaining vessels, only the Northwind was immediately available, as the Burton Island was still in service and the Eastwind was scheduled for service in the Arctic. By default, the Northwind would mean success or failure as the thrust began.

When it became apparent that the ice presented a serious danger to the Sennet, the submarine was towed back to Scott Island. The remainder of the group reached the Bay of Whales on , with the Northwind breaking out a harbor in the bay ice for them. Over the following two days, landing parties went ashore and selected a site for Little America IV, somewhat north of Little America III, the West Base of the à US Antarctic Service Expedition. Construction of the base and accompanying aircraft facilities commenced immediately thereafter. Quite an assortment of vehicles were used in this undertaking, including tractors, jeeps, weasels, bulldozers and other tracked equipment. On January 21, young sailor Vance Woodall, from the Yancey, was working on the ice in the unloading area when a tractor nearby picked up a load of snow roller sleds to move in to the barrier cache area. The D6 tractors were proving too heavy to ride on top of the snow that lay on the surface of the bay ice. In order to gain sufficient towing purchase, the drivers had to let the steel treads plow into the snow until reaching the hard ice. As a result, one tread would often grip the ice before the other, throwing the tractor violently from side to side until both treads took equally. The official accident report states that Woodall unfortunately caught both his right arm and head in the slats of the roller just as the tractor suddenly lurched ahead. Woodall's spinal column was severed "high in the neck" and the navy veteran of only seven months died instantly. By February 6 Little America consisted of a multitude of tents, a sole Quonset hut, three compacted snow runways and a short airstrip made of steel matting. At one point, the number of persons stationed at the base approached 300, but eventually this number had to be greatly reduced so that the remaining individuals could be readily evacuated by the Burton Island.

Dans le même temps, peut après midi le , le transporteur Philippine Sea, avec Byrd sur son pont, slowly pulled away from the pier at the Norfolk Navy Base as bands played and the local command saluted farewell.

Le Philippine Sea had been finishing up a shakedown exercise off Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, when orders were

received that she would be participating in Operation Highjump. The brand new ship hurried north with an exuberant

crew cheering the news... this was certainly more exciting than routine shore leave in Hong Kong or Panama! But

what a task they had before them. Since she would be going through the canal, changes had to be made in the hull

and flight deck structures. A massive shipment of parts for twenty sleds came in from the Supply Office of the

Boston Navy Yard and quickly assembled for use by the Byrd party. A quantity of "Byrd cloth" was shipped in for

the construction of various items of cold weather clothing and equipment

. An HO3S1 helicopter was flown

aboard along with approximately one hundred tons of miscellaneous equipment for use by the other ships

participating in Highjump. Next came the six R4D transport planes. They were obviously too big to be flown in at

sea so it took a little imagination to get them aboard. Since there was no landing field adjacent to the dock, a

mile-long swath had to be cut right through the middle of the naval base, from the field to the docks. What a site

it was as drivers had to "pilot" the planes through the narrow pathway, with sailors sitting on the wings to

prevent a sudden burst of wind from picking the plane up and hurling it against the sides of buildings, fences and

machinery, often within inches of the wingtips. Last aboard would be Byrd, just hours before shoving off.

The Philippine Sea reached the Canal Zone on , and the next day started the slow journey through the locks. Byrd and his men departed Balboa for the Antarctic on January 10. The ship steamed south at twenty knots toward Scott Island. By the vessel had reached 58°48'S, and "it was assumed icebergs could be encountered during the day". One of the helicopters was readied for takeoff and as it lifted from the deck, the pilot neglected to gain further altitude before veering off to the side of the carrier. As the copter swept over the port side, the sudden down-wash of wind, together with the loss of the flight deck surface as a cushion, sucked the aircraft right into the water. Fortunately the pilot bailed out and was rescued by a lifeboat. On , they rendezvoused with the Northwind, Cacapon, Sennet and Brownson near Scott Island. Four days later, on , the first two R4D's successfully took off from the flight deck of the Philippine Sea for the risky flight to Little America IV; Admiral Byrd was aboard the first plane. By , all six R4D's had arrived safely at Little America IV. The carrier's objective had now been completed. Carrying the only outbound mail from Highjump ships during their Antarctic deployment, the Philippine Sea turned and headed for Balboa, Canal Zone. She arrived there on and ten days later was back at Quonset Point, Rhode Island.

Back at Little America, every opportunity was taken to keep the aircraft flying. Several photographic missions were flown, including a two-aircraft flight to the South Pole on à . A final flight attempt was made on , but was turned back due to poor weather, thus terminating Little America-based flight operations for the expedition. On the ground, investigations were conducted in the immediate vicinity of Little America. A tractor party departed Little America for the Rockefeller Mountains on , but had to return prematurely to the base a week later due to the impending evacuation.

Finally completing shakedown trials, the Burton Island departed San Diego, California at By she had reached the northern edge of the Ross Sea pack. Two days later she contacted the ships of the Central Group at 72°S and delivered mail for these vessels. On she headed for McMurdo Sound, arriving on , where she acted as a weather station until the . Following this duty, she steamed for Little America to commence evacuation of the base. The Burton Island reached Little America on February 22 and evacuation operations commenced immediately. The remaining base personnel boarded the icebreaker shortly thereafter, and she departed the Bay of Whales on .

Les vaisseaux du Groupe Central empruntent diverses routes pour le trajet de retour. Le Merrick received extensive rudder damage from the ice floes and had to be towed by the Northwind back to Port Chalmers, New Zealand, for repairs. All the ships had taken a significant amount of abuse from the ice. The bows and sides of the flagship and cargo vessels Merrick and Yancey became severely dented, as rivets were sprung and propellers damaged. Nevertheless, they all made it back. The Merrick was in drydock for a month but eventually sailed north on , arriving in San Diego on . Dans le même temps, le Northwind, Mount Olympus et Burton Island partent de Wellington (Nouvelle Zélande) le . Le Northwind arrive à Seattle (Washington) le 6 Avril 1947. Le Burton Island arrive à San Pedro (Californie) le et le Mount Olympus slipped through the Canal on and arrived in Washington, D.C. le . Le Yancey a un voyage de retour plus intéressant. Il quitte Port Chalmers le et arrive à Pago Pago (Samoa) le . Il quitte Samoa le and steered for Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, with the Navy YTL-153 in tow. Under steam at about 7.5 knots, elle arrive à Pearl le . Le long voyage pour l'équipage et le navire se termine finalement le , lorsqu'il débarquent à Port Hueneme (Californie). Le sous-marin Sennet served as a stand-by rescue vessel for the R4D flights from the Philippine Sea to Little America through the . On she set course for Wellington, New Zealand. Elle quitte la Nouvelle-Zélande le 15 Février et arrive son mouillage à la Base Sous-Marine de Balboa, Canal Zone, le .

Les activités du Groupe Occidental

Le rendez-vous du Groupe Occidental aux Iles Marquises le , and sailing on parallel paths,

they reached the edge of the pack ice northeast of the Balleny Islands on Christmas Eve day. The Henderson and

Cacapon fanned out to serve as weather stations while flight operations from the Currituck began on December 24.

Perhaps Dufek and his men struggled with the Antarctic elements off the Thurston Peninsula, but Captain Charles A.

Bond and his Western Group were blessed by comparison. Their primary weather problem was related to fog.

Additionally, considering that none of the sailors aboard the three ships and ever seen Antarctic service before,

things couldn't have gone much better. Captain John Clark of the Currituck wrote, "The acute personnel situation

then current in the Navy by reason of the demobilization fully affected this vessel". Of major concern was the

Engineering Department, where the inexperienced men were encountering numerous difficulties with all phases of

the plant. The ship was to continue to be handicapped by critical personnel shortages throughout the entire

operation

. The handling of the PBM's were a concern, too. A continuous and searching analysis was made of

all phases of plane handling

. Clark was acutely aware of the special weather conditions encountered in the

South Polar region and the need to "reduce all plane handling times to a minimum except crane operating time and

that of actual fueling from the ship's side, which were, or course, uncontrollable". With much practice, the plane

handling time was actually cut by two-thirds.

A few flights were attempted but fog continued to plague them until . The fog lifted and

the first mapping flight of about seven hours was flown along the Oates Coast with complete success. Free from

fighting the elements his colleague Dufek was encountering, Bond was able to concentrate his attention on

mastering the weather. The ship was continuously looking for good weather and for ice bays in the pack ice for

wind protection, being guided in the former by the aerologist's recommendations

. The pilots were encouraged

and enthused by Bond's leadership and the resulting accuracy of the aerology and radar tracking teams, both on the

Currituck and aboard the aircraft. Whereas the pilots at Little America IV fought dense cloud formations rising to

thirteen or fourteen thousand feet, the Western Group, flying along Wilkes Land, found that even if the overcast

was dense, ordinarily you would break out in the clear soon. On the average the cloud layer wasn't any more

than 4 or 5000 feet thick with not too much icing . . . it would be absolutely clear on top

.

Icebergs were encountered, but as Clark recalled, Bergs were shown by radar with fidelity and the ship

maneuvered in and out among them easily

. Bond was pleased as significant air operations resulted in

unquestioned successes. After the seven-hour mission on New Years Day, flights were made on the 2nd, 4th, 5th and

6th over the continent from their staging area in the Balleny Islands. "Operations were eminently successful and a

substantial portion of the area assignment had been completed by this time". Their first assignment completed,

Cruzen radioed from the Central Group instructing Bond to cease operations and sail the Currituck eastward to the

vicinity of Scott Island in order to reconnoiter for the Northwind and its bedeviled flock in the Ross Sea. The

Currituck reached Scott Island on the 10th and both patrol planes flew reconnaissance missions on the 11th and

12th, but no leads could be seen for their trapped colleagues in the ice below. Dismissed by Cruzen after their

unsuccessful air operations, the Currituck headed west again past the Adélie Coast and on to Wilkes Land along the

Sabrina, Knox and Queen Mary Coasts.

Malheureusement, aucun vol ne fut possible entre à because of the huge northerly

swell. On January 22 the swells at last moderated and the weather remained acceptable for additional flights. Over

the next week, long and successful photomapping missions progressed to the west. Suddenly, on either January 30 or

February 1 (the record is unclear), PBM pilot Lieutenant Commander David E. Bunger lifted from the bay and headed

south for the continent some hundred miles distant. At this time the Currituck was off the Shackleton Ice Shelf on

the Queen Mary Coast of Wilkes Land. Reaching the coastline, Bunger flew west with cameras humming. Suddenly the

men in the cockpit saw a dark spot come up over the barren white horizon and as they drew closer, they couldn't

believe their eyes. Byrd later described it as a "land of blue and green lakes and brown hills in an otherwise

limitless expanse of ice". Bunger and his men carefully inspected the region and then raced back to the ship to

tell the others of their discovery. Several days later Bunger and his flight crew returned for another look,

finding one of the lakes big enough to land on. Bunger carefully landed the "flying boat" and slowly came to a

stop. The water was actually quite warm for Antarctica, about 30°, as the men dipped their hands in to the elbow.

The lake was filled with red, blue and green algae which gave the lakes their distinctive color. The fly boys seemed

to have dropped out of the twentieth century into a landscape of thousands of years ago when land was just

starting to emerge from one of the great ice ages

, Byrd later wrote. Byrd called the discovery by far the

most important, so far as the public interest was concerned . . . of the expedition

. Dès ,

les hommes se demandaient alors s'il s'agissait des premiers signes d'un réchauffement climatique. As Paul Siple

disgustingly reported, discussion between the scientists as to the nature of "Bungers Oasis" had not even begun

"before the eleven press representatives aboard the Mount Olympus had fired off dispatches to the outside world

describing the oasis as a 'Shangri-La' and implying that it was warmed by a mysterious source of heat and might be

supporting vegetation". Siple gave high marks to the crew of the PBM for landing and making an attempt to examine

the lake, however Bunger "had no technical tools to examine his find". He even had to guess the temperature of the

water since no thermometer was aboard. But they did have an empty bottle aboard which they filled with water from

the lake. Unfortunately, "the water in the bottle turned out to be brackish, a clue to the fact that the 'lake'

was actually an arm of the open sea".

A la fin , inclement weather had forced the airmen to skip over the existing gap between 150°E and 145°E longitude, which later expeditions would fill in. Mapping missions continued day after day covering a 1500-mile long area between 141°E and 115°E longitude. Wilkes Land proved to be a "featureless ice sheet that ranged from 6000 to 9500 feet above sea level. No mountains were lofty enough to thrust their heads into the frigid winds above this white blanket, although valleys and ridges in the ice surface up to 100 miles inland gave a hint of rough terrain underneath".

La méteo devint typiquement Antarctique avec la première semaine de . Les mers devinrent brutes

et les tempêtes de neige fréquentes et les opérations aériennes furent limitées à seulement 3 jours dans le mois.

Durant cette période, le Currituck vogua sur des centaines de miles autour de la côte, de 115° à 40° de

longitude Est, tout autour de Wilkes Land, le American Highland faisant face à l'Océan Indien et le Queen Maud

Land. Lorsque les avions purent à nouveau voler, des résultats outstanding results would be the norm. Ces

résultats seraient d'une importance significative pour la sélection des sites de bases quelques 10 ans plus tard

lors de l'IGY. Le , lorsque le Currituck fut au large

ed la Côte de la Princess Ragnhild de Queen Maud Land, les pilotes W. R. Kreitzer et F. L. Reinbolt décolèrent

dans leur PBM pour une mission photographique de routine visant à cartographier 300 miles de côte. What had

previously been drawn in as coastline now proved to be towering shelf ice rising high above the sea. As they

turned south, they suddenly discovered a range of ice-crystal mountains, luminously blue against the dark sky,

rising more than two miles into the air. Flying near the mountain peaks, Kreitzer and Reinbolt followed the range

for nearly one hundred miles before turning back. One of them later told Byrd, C'était comme le paysage d'une

autre planète

.

Le , the final flights were made in the vicinity of Ingrid Christensen Coast. The Cacapon fueled the Henderson and Currituck on March 3 and all three ships sailed for Sydney, Australia, arriving there on March 14. All three ships departed Sydney on March 20. The Currictuck arrived at the Canal Zone on April 9, traveled through the locks and arrived in Norfolk, Virginia on . The Henderson entered San Diego Bay channel on April 6 and the Cacapon arrived at San Pedro, Californie on .

Les activities du Groupe Oriental

Operations of the Eastern Group commenced in the vicinity of Peter I Island, north of the Bellingshausen Sea, late in . The Pine Island reported a position near Swain Island on and on Christmas Eve, the first iceberg was spotted. Without question, the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas experience some of the worst weather conditions in the world. To complicate matters with the Eastern Group, frequent foggy weather, howling blizzards and stormy waters made aircraft launching and flight perpetually hazardous. That portion of the global windstream that follows the north / south axis is heated in the tropics and rushed toward the poles in the upper atmosphere. The massive Antarctic ice cap cools this mass and as the air descends, greater cooling takes place. The frigid, cold air is deflected outward once it reaches the Pole. The natural rotation of the earth drives the air mass toward the coastline from a southeasterly direction, often creating hurricane-force winds in the process. Between Cape Leahy and Cape Dart and in the area around Mount Siple in the Amundsen Sea vicinity, this frigid howling windstream often slams head-on into a southward-heading warmer air mass blowing in from the lower Pacific. As a result, a cyclone is created which spins eastward along Ellsworth Land and through the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas, gathering velocity as it races up the base of the Antarctic Peninsula across Charcot Island and Marguerite Bay before finally dissipating along the tip of the peninsula or at sea in the Drake Passage.

Heavy swells and frequent snow squalls plagued the Pine Island until the weather suddenly improved and cleared in the afternoon of December 29. PBM George I was lowered over the side and fueled without difficulty and shortly after 1:00 p.m. the plane lifted off the water on the first flight to Antarctica with Lieutenant Commander John D. Howell as pilot and Captain George Dufek as observer. Within hours, George I radioed back that weather conditions were favorable for mapping operations over the continent and so George 2 took to the air later that evening. When George I returned at 11:05 p.m., a third flight was scheduled with an entirely new crew. This flight left at 2:24 in the morning of December 30 (it was, of course, daylight 24 hours / day), with Lieutenant (jg) Ralph Paul "Frenchy" LeBlanc at the controls. His co-pilot was young Lieutenant (jg) Bill Kearns. The rest of the crew consisted of navigator Ensign Maxwell Lopez, Aviation Radioman Second-Class Wendell K. Hendersin, flight engineer Frederick W. Williams, photographer Owen McCarty, mechanic William Warr, Aviation Radioman Second-Class James H. "Jimmy" Robbins and lastly, the skipper of the Pine Island, Captain Caldwell.

Alors que George I volait en direction du Sud-Ouest à 400 pieds au-dessus de la glace, le temps semblait

tout sauf prometteur

, comme l'écrivit plus tard Kearn. L'avion vola durant 3 h avant de rejoindre la côte de

Thurston Island (alors appelée la Péninsule de Thurston). Le co-pilote Kearns prit les commandes d'un LeBlanc très

fatigué et amena l'avion à 1000 pieds d'altitude. Malheureusement, l'avion commença à rejoindre une grande partie

de glace. Le plexiglas de la station à l'avant gela et les vitres du cockpit gelèrent malgré tous les efforts de

l'équipement de dégrivrage à bord. L'avion pénétra soudainement dans un "aveuglement glacé", streams of sunshine

trapped beneath the clouds, bouncing off the snow "in a million directions, as if each ice fragment were a tiny

mirror". To make matters worse, a fine, driving snow obstructed the surface below. Puzzled in their predicament,

the altimeters began giving different readings and as the wings began to ice up, Kearns turned to LeBlanc and

said, "I don't like the looks of this. Let's get the hell out of here!" LeBlanc nodded in agreement and as Kearns

gently banked the plane, all on board felt a "crunching shock" that "reverberated all along the hull". The plane

had obviously grazed something so Kearns immediately applied full throttle as LeBlanc gave full low pitch to the

propellers to aid pulling power. Both men pulled back hard on the yoke and George I began to rise steeply. Then

the "flying boat" blew up.

The plane had literally blown apart. Three of the men were dead and the others crawled into what was left of the fuselage to lay stunned and bleeding for hours. The explosion had lifted co-pilot Kearns right out of his seat, whose seat belt was unfastened for the first time in all his years of flying. He flew right out the cockpit window, headed straight for the starboard propeller and somehow missed the blade and instead fell harmlessly into the drifting snow. Landing like a ski jumper, Kearns fell head-over-heels down a slope and when he awoke from his daze, "I was all in one piece -- just full of pain and nearly frozen". All but one of the crew had been blown clear of the wreck. Captain Caldwell had been riding in the nose of the plane when he was pitched out the window and into the snow. His wounds were relatively minor: a cut across the nose, several chipped and loosened teeth and a broken ankle. McCarty had a 9 ½" gash in his scalp which knocked him unconscious for about an hour. He woke up to extreme pain in his right hand caused by a dislocated thumb and when he went to stand up, he could not lift his leg. Warr had suffered only a small cut on his scalp and radioman Robbins came out of the ordeal with only post-crash shock. The other four men were not so lucky. LeBlanc was still in the shattered and burning cockpit, his body held in the grips of his seat belt. Flames from the burning aviation fuel were licking at LeBlanc's body as Kearns reached the wreckage first and rushed through the fire to undo the seat belt. As hard as he tried, Kearn's stiff shoulder wouldn't allow him to set LeBlanc free. Robbins rushed forward to assist and between them, LeBlanc was finally freed. Kearns, Robbins and Warr used their gloved hands to beat the fire out that was consuming LeBlanc's body. Kearns later recalled, "Frenchy's face, arms and legs were burned black and were already starting to swell. He was only half-conscious, writhing in pain and muttering unintelligibly". LeBlanc was covered with a parachute and the search resumed for the others. It was a gruesome find. The official report states that Hendersin died instantly of "extreme multiple injuries" and that Williams went about 2 ½ hours later from the same trauma. Lopez was decapitated ("traumatic amputation of the head"). These were the first men to ever die on an Antarctic expedition connected in any way with Richard E. Byrd.

Admiral Byrd later wrote of the absolutely terrifying experience this must have been. None of them had ever been

to Antarctica before the crash and even though some of them had experienced similar flying conditions in the north

polar regions, One is generally introduced to Antarctica by degrees, and even then it is awe-inspiring. But

these young men came out of their daze -- woke up, as it were -- lying on the continent and in one of its most

uninhabitable spots. C'était comme mourrir et venir à la vie dans un autre monde

. McCarty wrote a farewell

letter to his family. He figured they'd be found someday and he wanted his wife to know what had happened. For a

day and a half the survivors slept or talked as though dazed by drugs. Incredibly, LeBlanc tried to cheer everyone

up as he called to McCarty, Now don't you worry, Mac. Just take it easy. They'll come and get us out of this

mess

. LeBlanc's pain finally drove him into delirium as he staggered to his feet so that he could go

below and see Doc Williamson

. Kearns and the others gently helped him back into his sleeping bag. The men

used the remaining section of fuselage as a shelter for the rest of their ordeal.

"Plane number one CW and voice call George One Captain Caldwell flight crew number three overdue since 30 1945 Z. Accordance rescue doctrine have made preparations for search and rescue". This message was radioed to Cruzen in the Central Group. Unfortunately, inclement weather stubbornly refused to allow for search flights. At the crash site, New Year's Eve was celebrated with Warr and Robbins scouring the wreckage for food. A little dried fruit was all that could be found. The next morning they awoke in a better mood and Robbins was able to find more food, frozen solid, along with a frying pan, pressure cooker and some canned heat, possibly enough for a few hot meals. After breakfast, McCarty looked through the wreckage for his wedding ring which had come off in the crash -- he found it. On January 2, the snow finally stopped. More food was discovered in the wreckage, enough to ensure survival for quite some time. The aircraft, in Kearns words, was "a virtual flying laboratory, carrying radar and other equipment far more elaborate than old-time explorers had dreamed of. Nine cameras were set up within her huge frame. Her emergency supplies included food packets, sleeping bags, field tents, medical equipment, and a survival sled. Within the sled were stored additional rations, warm clothing and small arms". The next few days broke clear and cold. On January 5, LeBlanc's condition had deteriorated as a supply of fresh water was now becoming a problem. LeBlanc's hands had swelled and his face had become covered with a hard, black crust. His legs and back had been left with a mass of angry burns. LeBlanc's biggest problem was dehydration and even though the men tried to keep a cup of water next to Frenchy, it would freeze in a matter of minutes. Huge quantities of snow were melted by the Coleman stove in order to obtain only a mouthful of water. This ordeal and daily suffrage would continue until January 11.

Operations aboard the Pine Island were frustrating, at best. On New Year's Day, George II was lifted over the side but a dense fog suddenly rolled in. The plane was tied up to the stern by a 300-foot line and at two the next morning, disaster struck. The swells swung the plane around and thrust it into the side of the ship, extensively damaging a wing tip, de-icing boot and aileron. By January 5, George II had been repaired and George III assembled for backup. Both planes were lowered over the side and once again the fog rolled in. Finally, the weather cleared and that afternoon a test flight was ordered. It went off without a hitch and later that evening a search was made over the last reported position of George I but they returned to the ship "because of increasingly bad weather". The following day weather conditions allowed a second flight, but once again the mission was scrapped due to fog and snow. Snow, fog and heavy swells continued to plague the search efforts until the 9th, but even the search that day was turned back due to "very unfavorable weather". Good fortune would finally smile on Dufek and his men on the morning of January 11. At 4:30 a.m., George II, flown by Lieutenant (jg.) James Ball and Lieutenant (jg.) Robert Goff, was hoisted over the side. It lifted from the water at 7:00 a.m. and flew off in the direction of the continent. Later, at the crash site, Kearns suddenly sat up and shouted "Airplane!" They struggled out of tents and the plane and there, on the horizon, was Ball's PBM. Everything that could burn, especially the raft, was dragged out of the plane. They waited and waited and two hours after the first sighting, Caldwell cried, "There she is, lads!" Robbins dropped a match on the pile of debris which sent a tall column of smoke high into the sky. The PBM rocked its wing and the men went hysterical, dancing and jumping in the snow. However, the ordeal was not over.

Supplies, including food, clothing, cigarettes, bedding, a rifle and ammunition, even two quarts of whiskey, came floating down by parachute. Then the survivors wrote a large message on the blue wing of the plane, letting those above know that Hendersin, Lopez and Williams had been killed. Meanwhile, co-pilot Goff of George II looked to the north for a landing spot. A few minutes later they returned and dropped a message in a sardine can, "Open water ten air miles to north. If you can make it on foot, join hands in a circle. If not, form straight line. Don't lost courage, we'll pick you up". "Let's go," Kearns said, and all but LeBlanc joined hands.

Ball and Goff, still overhead, were low on fuel and would have to return to the ship. No problem, as Lieutenant Commander Howell was already on his way in George III. Soon Howell was overhead dropping additional supplies to the men below. George III then went back to the shore and landed some two miles out. Conger and Howell loaded a sled and supplies into a life raft and gently lowered themselves into the sea for a brisk row to shore. Once ashore, the sled was loaded and the two men headed off into the interior. It was difficult going and as the two men trudged onward, the weather got colder and colder. Fog rolled in and the possibility of disaster loomed larger and larger. The survivors pushed their way along through huge snow drifts and as the fog drifted in ever closer, the men of George I dropped to the snow in exhaustion. Suddenly all heard a pistol shot. Robbins stood up and saw two figures moving toward them, dragging a sled. As Howell and Conger made their way to the six, they could not believe what they saw. Exhausted, bearded, battered men stood before them, overcome with pain and emotion. Howell quickly got the men moving. By this time, the fog had engulfed the plane and to make matters worse, it started snowing. The return trail was not marked and soon the earlier sled marks and footprints were covered. But fate stepped in at the last moment and the party suddenly arrived at the edge of the shore where they now would wait impatiently for the fog to lift. As it turned out, they would have to wait eight hours for the fog to lift enough for George III to be guided in. All were rowed out to the plane and several hours later the PBM was carefully hoisted aboard the Pine Island. All would recover but LeBlanc's legs would be amputated two weeks after the rescue aboard the carrier Philippine Sea.