Fermi 's Famous question, now central to debates

about the prevalence of extraterrestrial civilizations, arose during a luncheon conversation with Emil Konopinski,

Edward Teller, and Herbert York in the summer of en . Fermi

's Famous question, now central to debates

about the prevalence of extraterrestrial civilizations, arose during a luncheon conversation with Emil Konopinski,

Edward Teller, and Herbert York in the summer of en . Fermi 's companions on

that day have provided accounts of the incident.

's companions on

that day have provided accounts of the incident.

Part of the current debate about the existence and prevalence of extraterrestrials concerns interstellar travel and settlement [1-3]. In 1975, Michael Hart argued that interstellar travel would be feasible for a technologically advanced civilization and that a migration would fill the Galaxy in a few million years [4]. Since that interval is short compared with the age of the Galaxy, he then concluded that the absence of settlers or evidence of their engineering projects in the Solar System meant that there are no extraterrestrials.

Newman, Sagan, and Shklovski [2,5] recall that a legend of science says that Enrico Fermi asked the question, "Where are they?" during a visit to Los Alamos during the Second World War or shortly thereafter. Fermi's question has been mentioned in several other recent publications, but historical basis for the attribution has not been established. Thanks to the excellent memory of Hans Mark, who had heard a retelling at Los Alamos in the early 1950s, we now know that Fermi did make the remark during a lunchtime conversation about 1950. His companions were Emil Konopinski, Edward Teller, and Herbert York. All three have provided accounts of the incident.

We begin with Konopinski:

"I have only fragmentary recollections about the occasion.... I do have a fairly clear memory of how the discussion of extra-terrestrials got started while Enrico, Edward, Herb York, and I were walking to lunch at Fuller Lodge.

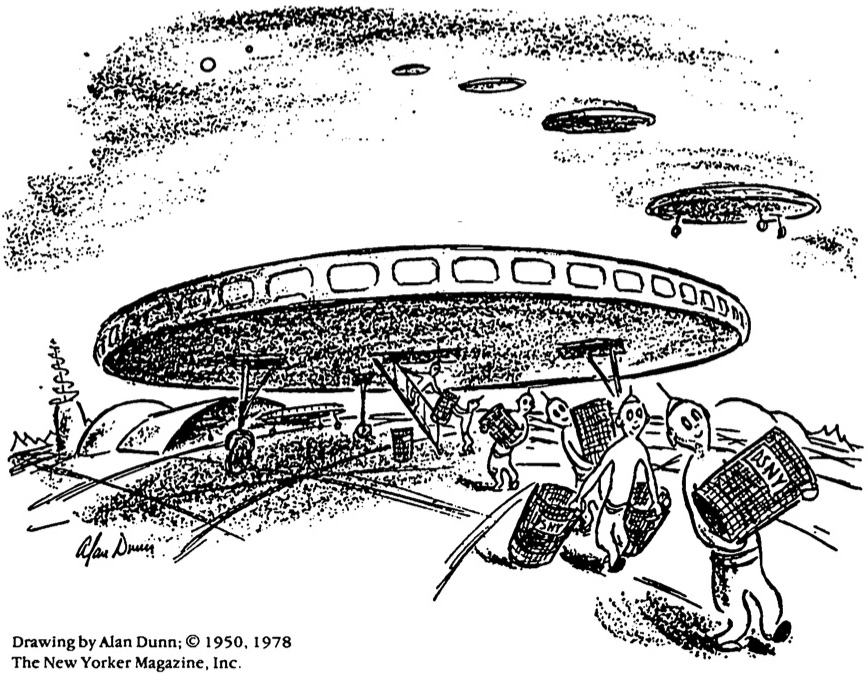

"When I joined the party, I found being discussed evidence about flying saucers. That immediately brought to my mind a cartoon I had recently seen in the New Yorker, explaining why public trash cans were disappearing from the streets of New York City. The New York papers were making a fuss about that. The cartoon showed what was evidently a flying saucer sitting in the background and, streaming toward it, 'little green men' (endowed with antennas) carrying the trash cans. More amusing was Fermi's comment, that it was a very reasonable theory since it accounted for two separate phenomena: the reports of flying saucers as well as the disappearance of the trash cans. There ensued a discussion as to whether the saucers could somehow exceed the speed of light."

Teller remembers:

My recollection of the event involving Fermi . . . is clear, but only partial. To begin with, I was there at the incident. I believe it occurred shortly after the end of the war on a visit of Fermi to the Laboratory, which quite possibly might have been during a summer.

I remember having walked over with Fermi and others to the Fuller Lodge for lunch. While we walked over, there was a conversation which I believe to have been quite brief and superficial on a subject only vaguely connected with space travel. I have a vague recollection, which may not be accurate, that we talked about flying saucers and the obvious statement that the flying saucers are not real. I also remember that Fermi explicitly raised the question, and I think he directed it at me, 'Edward, what do you think? How probable is it that within the next ten years we shall have clear evidence of a material object moving faster than light?' I remember that my answer vas ' 1 o-6.. Fermi said, 'This is much too low. The probability is more like ten percent' (the well known figure for a Fermi miracle.)

Konopinski says that he does not recall the numerical values, except that they changed rapidly as Edward and Fermi

bounced arguments off each other.

Teller continues: "The conversation, according to my memory, was only vaguely connected with astronautics partly on account of flying saucers might be due to extraterrestrial people (here I believe the remarks were purely negative), partly because exceeding light velocity would make interstellar travel one degree more real.

"We then talked about other things which I do not remember and maybe approximately eight of us sat down together for lunch." Konopinski and York are quite certain that there were only four of them.

It was after we were at the luncheon table," Konopinski recalls, "that Fermi surprised us with the question 'but where is everybody?' It was his way of putting it that drew laughs from us ."

York, who does not recall the preliminary conversation on the walk to Fuller Lodge, does remember that "virtually apropos of nothing Fermi said, 'Don't you ever wonder where everybody is?' Somehow . . . we all knew he meant extra-terrestrials."

Teller remembers the question in much the same way. "The discussion had nothing to do with astronomy or with extraterrestrial beings. I think it was some down-to-earth topic. Then, in the middle of this conversation, Fermi came out with the quite unexpected question 'Where is everybody?' . . . The result of his question was general laughter because of the strange fact that in spite of Fermi's question coming from the clear blue, everybody around the table seemed to understand at once that he was talking about extraterrestrial life.

"I do not believe that much came of this conversation, except perhaps a statement that the distances to the next location of living beings may be very great and that, indeed, as far as our galaxy is concerned, we are living somewhere in the sticks, far removed from the metropolitan area of the galactic center."

York believes that Fermi was somewhat more expansive and "followed up with a series of calculations on the probability of earthlike planets, the probability of life given an earth, the probability of humans given life, the likely rise and duration of high technology, and so on. He concluded on the basis of such calculations that we ought to have been visited long ago and many times over. As I recall, he went on to conclude that the reason we hadn't been visited might be that interstellar flight is impossible, or, if it is possible, always judged to be not worth the effort, or technological civilization doesn't last long enough for it to happen." York confessed to being hazy about these last remarks.

In summary, Fermi did ask the question, and perhaps not surprisingly, issues still debated today were part of the discussion . Certainly, the line of argument that York remembers became familiar a decade later as the Drake-Greenbank Equation [6,7].

A final point: the date of the conversation. York is clearest on the date. "The conversation was either in the summer of 1950, 1951, or 1952, very probably 1951, and took place . . . when I was visiting LASL in connection with the forthcoming Greenhouse tests - specifically, the George shot." The George test occurred on May 8, 1951, suggesting a 1950 date. Surviving correspondence from the time indicates that Fermi was an annual summer visitor during the years in question. Unfortunately, attendance and travel records for those years have been destroyed. However, we have the evidence of the cartoon Konopinski mentions. Drawn by Alan Dunn, it was published in the May 20, 1950, issue of The New Yorker. It seems quite probable that the incident of Fermi's question occurred in the summer of 1950.

I am grateful to Hans Mark and to the three surviving participants for their accounts. These accounts, together with my letters of inquiry, are reproduced in the following pages.