Introduction

Les astronautes en orbite voient la Terre, son atmosphère et le ciel astronomique depuis des altitudes variant de 100 à 800 + miles nautiques (160 à 1300 km) au-dessus du niveau de la mer, bien au-dessus des restrictions de l'observateur au sol. Ils sont compétents pour faire des observations précises, leur vision est excellente, ils sont particulièrement familiers avec l'astrononomie de navigation et ont un large compréhension des sciences physiques de base. Leurs rapports d'observations visuelles depuis une orbite sont donc à considérer avec toutes les attentions.

Entre le 1968 avril 1961 et le March 1969 novembre 1966, 30 astronautes ont passé un total de 2503 h en orbite (voir tableaux 1 et 2). Au cours des vols les astronautes se sont acquités de tâches affectées de diverses catégories générales, à savoir : de défense, d'ingéniérie, médicales et scientifiques. Une liste des tâches affectées qui faisaient partie du programme Mercury est fournie dans le tableau 3 pour donner une idée des types d'observations visuelles que l'on demandait de faire aux astronautes.

Dans le cadre du programme, des debriefings ont été tenus après chaque mission des US. A ces sessions, les astronautes furent interrogés par des scientifiques impliqués dans la conception des expériences sur leurs observations, non prévues aussi bien que spécifiquement prévues. Les debriefings complétaient les rapports sur le vif effectués par les astronautes pendant la mission dans les contacts radio avec le centre de contrôle au sol. De cette manière, un panorama détaillé était obtenu de ce que les astronautes avaient vu en orbite.

Ce chapitre discute des conditions dans lesquelles les astronautes ont observé, en particulier en référence aux séries Mercury et Gemini, et des observations, qu'ils avaient prevues ou non.

| Nom | Temps total en orbite | Désignation du vol s1[GT = Série des Gemini; MA and MR = Série des Mercury; les vols désignés par des mots commençant par "V" font référence aux vols soviétiques] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heures | Minutes | ||

| Aldrin | 94 | 34 | GT-12 |

| Armstrong | 10 | 42 | GT-8 |

| Borman | 330 | 55 | GT-7 |

| Belayeyev | 27 | 2 | Voshkod II |

| Bykovsky | 119 | 6 | Vostok V |

| Carpenter | 4 | 56 | MA-7 |

| Cernan | 72 | 21 | GT-9 |

| Collins | 70 | 47 | GT-10 |

| Conrad | 262 | 13 | GT-5, GT-11 |

| Cooper | 225 | 16 | MA-9, GT-5 |

| Feoktisov | 24 | 17 | Voshkod I |

| Gagarin | 1 | 48 | Vostok I |

| Glenn | 4 | 56 | MA-6 |

| Gordon | 71 | 17 | GT-11 |

| Grissom | 5 | 10 | MR-4, GT-3 |

| Komarov | 24 | 17 | Voshkod I |

| Leonov | 27 | 2 | Voshkod II |

| Lovell | 425 | 29 | GT-7, GT-12 |

| McDivitt | 97 | 50 | GT-4 |

| Nikoyalev | 94 | 35 | Vostok III |

| Popovich | 70 | 57 | Vostok IV |

| Schirra | 35 | 4 | MA-8, GT-6 |

| Scott | 10 | 42 | GT-8 |

| Shepherd | 0 | 15 | MR-3 |

| Stafford | 98 | 12 | GT-6, GT-9 |

| Tereshkova | 70 | 50 | Vostok VI |

| Titov | 25 | 18 | Vostok II |

| White | 97 | 50 | GT-4 |

| Yegorov | 24 | 17 | Voshkod I |

| Young | 75 | 41 | GT-3, GT-10 |

| Total (pour 30 astronautes) | 2503 | 39 | Total des vols habités 37 |

| Vol | Astronautes | Date de lancement | Nombre de révolutions | Durée | Altitude (miles statutaires) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | mn | Périgée | Apogée | ||||

| Vostok I | Gagarin | 12 Avril 1961 | 1 | 1 | 48 | 110 | 187 |

| MR-3 | Sheperd | 5 Mai 1961 | Suborbital | 15 | 116 | - | |

| MR-4 | Grissom | 21 Juillet 1961 | Suborbital | 16 | 118 | - | |

| Vostok II | Titov | 6 Août 1961 | 17 | 25 | 18 | 100 | 159 |

| MA-6 | Glenn | 20 Février 1962 | 3 | 4 | 56 | 100 | 162 |

| MA-7 | Carpenter | 24 Mai 1962 | 3 | 4 | 56 | 99 | 167 |

| Vostok III | Nikoyalev | 11 Août 1962 | 64 | 94 | 35 | 114 | 156 |

| Vostok IV | Popovich | 12 Août 1962 | 48 | 70 | 57 | 112 | 158 |

| MA-8 | Schirra | 3 Octobre 1962 | 6 | 9 | 13 | 100 | 176 |

| MA-9 | Cooper | 15 Mai 1963 | 22 | 34 | 20 | 100 | 166 |

| Vostok V | Bykovsky | 14 Juin 1963 | 81 | 119 | 6 | 107 | 146 |

| Vostok VI | Tereshkova | 16 Juin 1963 | 48 | 70 | 50 | 113 | 144 |

| Voshkod I | Komarov, Yegorov, Feoktisov | 16 Octobre 1964 | 16 | 24 | 17 | 110 | 255 |

| Voshkod II | Belayayev, Leonov | 18 Mars 1965 | 17 | 27 | 2 | 107 | 307 |

| GT-3 | Grissom, Young | 23 Mars 1965 | 3 | 4 | 54 | 100 | 139 |

| GT-4 | McDivitt, White | 3 Juin 1965 | 63 | 97 | 50 | 100 | 175 |

| GT-5 | Cooper, Conrad | 21 Août 1965 | 120 | 190 | 56 | 100 | 189 |

| GT-6 | Schirra, Stafford | 15 Décembre 1965 | 16 | 25 | 51 | 100 | 140 |

| GT-7 | Borman, Lovell | 4 Décembre 1965 | 205 | 330 | 55 | 100 | 177 |

| GT-8 | Armstrong, Scott | 16 Mars 1966 | 7 | 10 | 42 | 99 | 147 |

| GT-9 | Stafford, Cernan | 3 Juin 1966 | 46 | 72 | 21 | 99 | 144 |

| *GT-10 | Young, Collins | 18 Juillet 1966 | 44 | 70 | 47 | 99 | 145 |

| *GT-11 | Conrad, Gordon | 12 Septembre 1966 | 45 | 71 | 17 | 100 | 151 |

| GT-12 | Lovell, Aldrin | 11 Novembre 1966 | 59 | 94 | 34 | 100 | 185 |

| Total (de 24 vols) | 934 | 1457 | 56 | ||||

* Les altitudes extrêmes de 475 et 850, respectivement, furent atteintes dans GT-10 et GT-11 by powered departures from the "stable" orbits indicated by the perigee and apogee given in the table.

| Observations affectuées | Numéros de missions | Equipement | Résultats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observe dimlight phenomena pour accroître notre connaissance des aurores, comètes faint près du Soleil, limite de magnitude faint des étoiles, gegenschein, libration, nuages, éclairs de météorites, lumière zodiacale. | 6, 9 | Oeil nu, Camera, Photomêtre voasmêtre | MA-6 pas adapté à l'obscurité. MA-9 saw zodiacal light and airglow. Photographs of airglow obtained. |

| Mesure de l'atténuation atmosphèrique de la lumière du Soleil et de l'intensité de la lumière des étoiles. | 6 | Photomêtre voasmêtre | Aucun résultat. |

| Déterminer les intensité, distribution, structure, variation et couleur de visual airglow. | 6, 7, 8, 9 | Oeil nu avec appareil photo filtre 5577-A | Airglow was seen on all flights; fut photographié sur MA-9. Filtre fut utilisé sur MA-7. |

| Déterminer le danger d'impact de micrométéorites et relier à la protection d'appareil spatial. | 6, 7, 8, 9 | Inspection visuelle et microscopique | 1 impact trouvé sur fenêtre de MA-9. |

| Déterminer intensité, distribution, structure, variation et couleur de red airglow. | 8, 9 | Oeil nu | Détecté visuellement sur MA-8 ; confirmé visuellement sur MA-9 |

| Tester et affiner la théorie de l'optique vis à vis de la réfraction des images près de l'horizon. | 6, 7, 9 | Oeil nu, appareil photo | Photographies MA-6, MA-7. Visuel MA-7, MA-9. |

| Déterminer la nature et la source de ce qu'on appelle "effet Glenn" ou de particules. | 6, 7, 8, 9 | Oeil nu, Camera | Découverte sur MA-6; toutes les autres observées visuellement ; photographies MA-7. |

| Comparer les observations d'intensités d'albedo, de jour et de nuit avec la théorie et affiner la théorie. | 6 | Oeil nu, Photomêtre voasmêtre | Non obtenu à cause d'un mauvais fonctionnement des instruments |

| Photographier la structure des nuages pour comparaison avec photos Liros. Améliorer prévision sur cartes. | 6, 7, 8, 9 | Appareil photo avec filtres de diverses longueurs d'onde | MA-8 et MA-9 ont obtenu les photographies prévues. |

| Take general weather photographs and make general meteorological observation for comparison with those made by Liros satellite. | 6, 7, 8, 9 | Oeil nu, Camera | All obtained photographs. |

| Determine best wavelength for definition of horizon for navigation. | 7, 9 | Camera avec filtres rouge et bleu | Successful. The red photographs were sharper; the blue more stable. |

| Obtain ultraviolet spectra of Orion stars for extension of knowledge below 3000 A | 6 | Ultraviolet spectrograph. | Spectra were obtained but window did not transmit to expected wavelength. |

| Identify geological and topographical features from high altitude photographs for comparison with surface features as mapped. | 6, 7, 8, 9 | Oeil nu, camera | Photographs obtained on all. Quality best on MA-9. |

| Identification of photographs of surface targets by comparison with known geological features. | 8 | Oeil nu, Camera | Few selected ones obtained. Quality fair. |

Les sources d'information sont :

- les rapports officiels de la National Aeronautics and space Administration (voir références),

- les transcriptions des discussions de presse pendant et après les missions

- les commentaires de mission diffusés systématiquement à la presse pendant les missions

- les transcriptions des rapports des astronautes basées sur les enregistrements réalisés peu après le retour de mission

- des notes personnelles faites par moi-même lors de briefings et debriefings scientific des astronautes, et

- les conversations avec nombre des astronautes.

Le vaisseau spatial comme observatoire

Les conditions dans lesquelles les astronautes font leurs observations sont sembables à celles qui seraient rencontrées par 1 ou 2 personnes à l'avant d'une petite voiture n'ayant pas de fenêtres sur les côtés ni à l'arrière et un pare-brise partiellement couvert, taché.

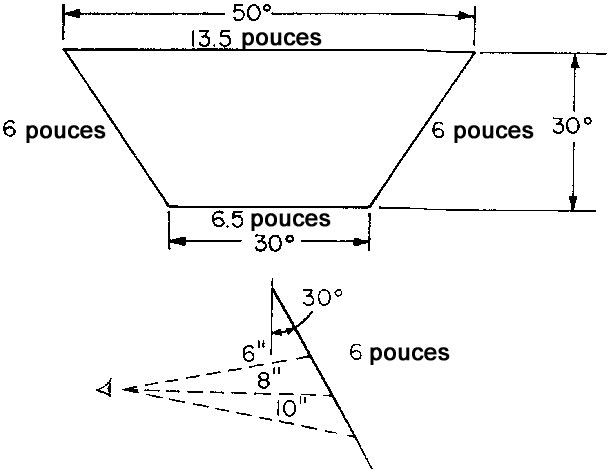

Les dimensions et configuration des fenêtres de l'appareil spatial, qui sont inclinées à 30 à vers les astronautes, sont données en Figure 1. Les fenêtres sont petites et ne permettent qu'une vue du ciel en avant limitée (concernant les astronautes). La sphère de vue autour d'une capsule dans l'espace contient 41253 degrés carrés, mais les astronautes sont capables de voir seulement 1200 degrés carrés ou environ 3 % de cette sphère ; et seulement 6 % d'un hémisphère. L'appareil spatial peut être tourné pour permettre aux astronautes de voir une zone différente que celle à laquelle ils font face, mais le carburant doit être conservé et les manœuvres ne sont habituellement pas effectuées pour fournir une vue meilleure ou différente. De fait, cependant, 94 % de l'angle solide de l'espace autour de la capsule a été, à tout moment donné, hors de vue des occupants de l'appareil spatial.

En plus du champ de vision restreint, les fenêtres elles-mêmes n'étaient jamais entièrement propres, et les difficultés imposées par the scattering of light from deposits on the window were severe. The deposits apparently occurred during the firing of third-stage rockets, when gases were swept past the windows. Attempts were made to eliminate the smudging by use of temporary covers jettisoned once orbit was achieved, but even then deposits were present on the inside of the outer pane of glass. Another source of contamination was apparently the material used to seal the glass to the frames. The net result was that the windows were never entirely clean, and scattered light hampered the astronautes' observations.

There were differences from one flight to another in viewing quality of the windows and from one window to the other on the same flight. Par exemple sur Gemini 7, the command pilot in the left seat was able to identify stars to magnitude 6 during satellite night, while the pilot in the right seat was limited to magnitude 4,4. The difference of 1,6 magnitudes (a factor of 4,4) was undoubtedly due to a difference in window transmission. It should be noted that stars as faint as magnitude 6 can be identified from the ground only under superb conditions (absence of artificial lights and moonlight plus a very clear sky).

The astronautes who had relatively clean windows often referred to the appearance of the night sky as seen in orbit, as similar to that seen by the pilot of a jet aircraft at 40000 pieds.

The smudged windows affected the visibility of objects during satellite night due to the decrease in the window transmission, but the effect was even more serious during satellite daytime when the glare from the light scattered by the smudge often was so bright as to destroy the contrast by which objects could be easily distinguished.

Dynamique orbitale

Les satellites en orbite sont sujets à atmospheric drag, qui finit par provoquer leur réentrée dans l'atmosphère de la terre, produisant souvent un display brillant alors qu'ils le font. Les réentrées sont parfois signalées en tant qu'ovnis. Un cas récent en particulier tient lieu d'exemple d'une réentrée rapportée comme un ovni et par la suite identifiée tentatively comme les réentrées de l'Agena de Gemini 11 (cas 11) et Zond IV (voir Section 6, Chapitre 2).

L'espace de 100 à 1000 km n'est pas un vide parfait, pas plus qu'il n'est isotherme. Vers 100 km the mean molecular weight de l'atmosphère undergoes a marked change, where O2 becomes dissociated by sunlight into atomic oxygen (voir Fig. 2). Jusqu'à 100 km environ le profil de température varie entre 200 °K environ et 300 °K. Au-dessus de 100 km la température undergoes a steady increase to 1000 °K. ou plus. La Fig. 3 montre comment la densité relative de l'atmosphère varie avec l'altitude jusqu'à hauteur de 1000 km. Au-dessus de 200 km la densité est sensitive to the asymptotic high-level temperature, too, which varies with the solar cycle and geomagnetic activity.

Si la Terre était une sphère parfaite et si il n'y avait pas de atmospheric drag, les satellites en orbite autour de notre planète se comporteraient selon les Lois de Kepler des orbites planétaires autour du Soleil. Le tableau 4 est dérivé de la 3ᵉ loi de Kepler. La relation entre la période en s (p) et la distance moyenne en cm (r) est exprimée par :

| p2 = | 4 pi2 r3

G ME |

= 0.9906 x 10-19 r3 |

où G, la constante gravitationnelle, est de

| S = | 2 à Pi à r

p |

= | 1.996 x 1010

sqrt(r) |

En appliquant la 3ᵉ loi de Kepler nous avons impliqué la validité des 2 premières lois de Kepler concernant les orbites de satellites ; i.e., que les satellites se déplaçent about la Terre en orbites elliptiques avec le centre de la Terre à un des foyers de l'ellipse ; et que le radius vector swept out by the satellite with respect to the center of the earth sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

The angular velocity of a satellite, (proportional to the reciprocal of the period), decreases as the radius of the orbit increases. Thus the process of docking, or flying in formation with a satellite already in a preceding orbit becomes a complicated and difficult maneuver involving descent to a lower, and therefore smaller, orbit with the resultant increase in angular velocity causing the following orbiting body to approach the preceding.

| Rayon de l'orbite | Période de l'orbite autour de la Terre | Vitesse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r (km) | P (s) | P (mn) | P (h) | P (j) | S (km/s) |

| 6378 + 200 | 5310 | 88,5 | 7,78 | ||

| 6378 + 500 | 5677 | 94,6 | 7,61 | ||

| 6378 + 1000 | 6307 | 105,1 | 7,35 | ||

| 6378 + 35,862 | 86,400 | 24 | 3,07 (géostationaire) | ||

| 6378 + 378,025 | 2372 x 106 | 27,4 | 1,02 (Lune) | ||

* mean radius of earth = 6378 km.

La drag atmosphèrique ralenti la vitesse du satellite, en particulier près du périgée, et ceci amène le satellite à swing out à une autre apogée plus petite. L'orbite se contracte et devient plus circulaire. Finalement le satellite descend à une altitude où the drag amène le satellite à réentrer dans l'atmosphère terrestre.

Le tableau 5 montre des décélérations calculées pour un objet massif comme un satellite, et une petite particule météoritique de 0,1 cm de diamêtre et de densité de 0,4 gm/cm-3 (masse = 2,09 x 10-4 g). À 160 km (le périgée de nombre des orbites des appareils contrôlés) la décélération sur le vaisseau spatial n'est pas trivaile (0,017 cm/sec-2) et l'orbite se dégradera lentement, mais sûrement en une réentrée. Intéressante par rapport à l'observation de petites particules par les astronautes est l'accélération différentielle entre le vaisseau et les particules. En une période de 10 s de petites particules "dériveront" loin de l'appareil jusqu'à une distance de plusieurs mêtres. Des vitesses relatives typiques de petites particules par rapport au vaisseau ont été estimées par les astronautes à 1 ou 2 m/s.

Lors de la réentrée, le vaisseau et les fragments émaillant sa surface deviennent lumineux, produisant les displays parfois signalés comme ovnis. Une réentrée de satellite intervient normalement le long d'une trajectoire grazing, mais les trajectoires de météorites sont plus radiales, et par conséquent la durée de luminosité ne dépasse généralement pas 2 ou 3 s.

Le tableau 6 montre les masses d'objets pour des magnitudes stellaires apparentes données et diverses périodes de luminosité, calculées en supposant que la totalité de l'énergie cinétique orbitale de l'objet est convertie en lumière suite à sa décéleration lors de la réentrée.

| Satellite | Petite particule | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masse (g) | 3,63x106 | 2,09x10-4 | ||

| Diamêtre (cm) | 400 | 0.1 | ||

| Ratio, aire/masse | 0,00865 | 37,5 | ||

| Altitude (km) | 160 | 200 | 160 | 200 |

| Densité de l'air | 8,271x10-13 | 1,098x10-13 | 8,271x10-13 | 1,098x10-13 |

| Décélération (cm-sec-2) | 1,741x10-2 | 2,311x10-3 | 18,86 | 2,50 |

| Séparation de l'appareil après : | ||||

| 1 s | 1,25 cm | |||

| 10 s | 125 cm | |||

| 100 s | 12500 cm | |||

Luminosité des objets éclairés par le Soleil

Des astronautes have reported observations they have made, while in orbit, of artifacts (defined here as man-made objects) as well as observations made of natural geophysical and astronomical phenomena during flight. It is among the observations of artifacts that unidentified sightings are most likely to occur, if at all.

A man-made satellite moving slowly against the star background has become a familiar sight. Even though the sun may be below the observer's horizon, the satellite, some hundreds of kilometers above the earth's surface catches the sun's rays and reflects them back to the ground-based observer. Since artifact sightings made from a spacecraft are frequently also the result of reflection of sunlight from a solid object, the question of the brightness of objects illuminated by the sun is pertinent to the consideration of observations from the space vehicles. One observation was reported of a dark object against the bright day sky (window?) background (see Section 9 of this chapter).

Satellite brightness, as observed from the ground, is usually given in apparent stellar magnitudes because of the convenience of comparing a satellite with the star background. The Oeil nu on a clear moonless night can perceive magnitudes as faint as between +5 and +6. Telescopic satellite searches are able to detect fainter magnitudes; for example, the United Kingdom optical tracking stations can acquire satellites as faint as +9 s2Pilkington, J. A.: "The visual appearance of artificial earth satellites," Planetary and Space Science, vol. 15, (1967), 1535.. The brightness of artificial satellites and their visual acquisition has been discussed by several writers (s3Pilkington, J. A.: "The visual appearance of artificial earth satellites," Planetary and Space Science, vol. 15, (1967), 1535.; Roach, J.R., 1967; Sumners, et al, 1966; and Zink, 1963).

Plots of the apparent visual magnitude of sun-illuminated objects as a function of slant distance (in kilometers) and of diameter (in centimeters) of the object are shown in Figs. 4 and 5 respectively.

| Durée de visibilité (Vitesse Initiale = 30 km/s) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnitude apparente | 1 s | 10 s | 100 s |

| 5 | 0,000078 g | 0,00078 g | 0,0078 g |

| 0 | 0,0078 g | 0,078 gm | 0,78 g |

| -5 | 0,79 g | 7,8 g | 78 g |

| -10 | 79 g | 780 g | 7800 g |

| Durée de visiblité (vitesse initiale = 7,5 km/s) | |

|---|---|

| Magnitude apparente | 100 s |

| -5 | 1000 g |

| -10 | 100 000 g |

In curve A of Fig. 4 and in Fig. 5 the illuminated object is assumed to be a sphere. In curve B of Fig. 4 the object is the Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO) with its sails broadside to the observer (Roach, J.R., 1967). The plots for the sphere are based on the assumption that a sun-illuminated sphere of diameter 1 meter at a distance of 1000 kilometers has an apparent magnitude of 7.84 s4Pilkington, J. A.: "The visual appearance of artificial earth satellites," Planetary and Space Science, vol. 15, (1967), 1535.. From this, a general relationship between apparent magnitude, m, diameter, d in meters, and slant distance, r in kilometers, is obtained:

La figure 5 indique que des artefacts de 1 m de diamêtre sont plus lumineux que m = +5 et par conséquent visibles pour l'œil nu normal à des distances de 100 km. Le même appareil spatial devient plus lumineux que Vénus à her brightest (m = -3) if closer to the observer than 10 km. In the case of a non-spherical object with an albedo that is less than unity, equation (1) is only a guide and the references in the bibliography should be consulted for details.

La figure 5 est pertinente pour l'observation de "fireflies" de Glenn et l'"uriglow" et montre que seen close up, i.e.; entre 1 et 10 m, même des particules très petites illuminées par le Soleil sont dazzlingly bright.

Acuité visuelle des astronautes

Reports by the Mercury astronautes that they were able to observe very small objects on the ground aroused considerable interest in the general matter of the visual acuity of the astronautes. One of the criteria in the selection of the astronautes to begin with was that they have excellent eyesight, but it was not known whether their high level of visual acuity would be sustained during flight. Therefore, experiments were designed to test whether any significant change in visual acuity could be detected during extended flights. These experiments were carried out during Gemini 5 (8 jours) et Gemini 7 (14 jours).

An in-flight vision tester was used one or more times per day, and the results were compared with preflight tests made with the same equipment. In addition, a test pattern was laid out on the ground near Laredo, Tex. for observation during flight. The reader is referred to the original report for the details of the carefully controlled experiments, which led to the following conclusions:

Data from the inflight vision tester show that no change was detected in the visual performance of any of the four astronautes who composed the crews of Gemini 5 and Gemini 7. Results from observations of the ground site near Laredo, Tex., confirm that the visual performance of the astronautes during space flight was within the statistical range of their preflight visual performance and demonstrate that laboratory visual data can be combined with environmental optical data to predict correctly the limiting visual capability of astronautes to discriminate small objects on the surface of the earth in the daylight.

In addition, the astronautes' vision was tested both before and after the flights and the test results were compared with preflight measurements. There were no significant differences in the level of their acuity, as shown in the following tabulation of test results:

| Astronaute | Pré-vol | Post-vol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.S. | O.D. | O.S. | O.D. | ||

| Cooper | Far Near |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/20 |

20/15 20/20 |

| Conrad | Far Near |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/15 |

20/12.5 20/15 |

20/12.5 20/15 |

| Borman | Far Near |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/15 |

| Lovell | Far Near |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/15 |

20/15 20/15 |

It is clear that the men selected to participate in the space program of the U.S. have excellent eyesight and that the level of performance is sustained over long and tiring flights.

At the same time, a hindrance to top observing performance was that the astronautes were never thoroughly dark-adapted for any length of time. Good dark-adaptation is achieved some 30 mn after the eyes are initially subjected to darkness. A typical orbit period was 90 mn during which the astronautes were in full sunlight for 45 minutes and in darkness for 45 mn. The astronautes therefore were fully dark adapted for only 15 mn out of every 90 mn orbit (assuming no cabin lights).

Exemples d'observations de Phénomènes naturels

The Night Airglow

Le 1er américain à aller en orbite, l'astronaute John Glenn (MA-6), signala observer un anneau autour de l'horizon durant la nuit satellitaire. Cela lui sembla être plusieurs degrés au-dessus de la surface solide de la Terre et il remarqua que les étoiles semblaient s'obscurcir alors qu'elles se "couchaient" derrière la couche. L'astronaute Carpenter (MA-7) effectua des mesures mineutieuses de la hauteur angulaire de la couche au-dessus de la surface de la Terre et estimata sa luminosité. Tous les astronautes sont depuis devenus familiers du Phénomène. Peu après le signalement de Glenn (planche 13) l'anneau fut identifié comme une couche de airglow vue de manière tangentielle. Il est particulièrement notable lorsqu'il n'y a pas de Lune dans le ciel et que la surface solide de la Terre est à peine discernable (planche 14) ; de fait il est plus fcile d'utiliser la couche de airglow que le bord de la terre comme référence dans l'établissement de mesures au sextant d'élévations angulaires d'étoiles.

Ground-based studies of the night airglow show that it is composed of a number of separate and distinct layers. The layer visible to the astronautes is a narrow one at a height of about 100 km which, seen tangentially by the astronautes, is easily visible. (It can be seen from the earth's surface only marginally but is easily measured with photometers.)

At a height of about 250 km. there is another airglow layer which is especially prominent in the tropics. It is probable that airglow from this higher level was seen on two occasions. L'astronaute Schirra (MA-8) signala une faint luminosity of a patchy nature while south of Madagascar, looking in the general direction of India (NASA SP-12, page 53, 3 Octobre 1962) comme suit :

A smog-appearing layer was evident during the fourth pass while I was in drifting flight on the night side, almost at 32° south latitude. I would say that this layer represented about a quarter of the field of view out of the window and this surprised me. I thought I was looking at clouds all the time until I saw stars down at the bottom or underneath the glowing layer.

Seeing the stars below the glowing layer was probably the biggest surprise I had during the flight. I expect that future flights may help to clarify the nature of this band of light, which appeared to be thicker than that reported by Scott Carpenter.

All the astronautes of later flights knew of astronaut Schirra's sighting, but on only one other occasion was an observation made of a similar phenomenon. At 05h llm 34s into the Mercury flight, astronaut Cooper reported "Right now I can make out a lot of luminous activities in an easterly direction at 180° yaw ... I wouldn't say it was much like a layer. It wasn't distinct and it didn't last long; but it was higher than I was. It wasn't even in the vicinity of the horizon and was not well defined. A good size." I had occasion to query him a bit more about his report during a debriefing following the flight:

Roach:

More like a patch?Cooper:

Smoother. It was a good sized area.Roach:

You didn't feel this had a discrete shape?Cooper:

It was very indistinct in shape. It was a faint glow with a reddish brown cast.

The phenomenon was estimated to be at about 50° west longitude and about 0° latitude.

The hypothesis has been advanced that the two observations are of the tropical airglow. We know from ground observations of this phenomenon that it is often observed to be patchy. The spectroscopic composition of the phenomenon is about 80% 6300° and 20% 5577*Aring;. If a bright patchy region of 1000 km. extension (horizontal) came into the view of an astronaut it could appear to be "smog appearing" (Schirra) or "reddish brown" (Cooper). The tropical airglow was relatively bright during 1962 and 1963, and became quite faint during 1964 to 1966, the sunspot minimum. During 1967, as the new sunspot maximum approached, the tropical airglow underwent a significant enhancement. This solar cycle dependence could account for the fact that the Gemini astronautes (1965-1966), although-alerted to look for this "high airglow," did not see it.

The Aurora

The Mercury and Gemini orbits were confined within geographic latitudes of 32° N and 32° S. Since the auroral zones are at geomagnetic latitudes of 67° N and 67° S it would seem unlikely that auroras could be seen by the astronautes. However two circumstances were favorable for such sightings. First, the "dip" of the horizon at orbital heights puts the viewed horizon at a considerable distance from the sub-satellite point. For example at a satellite height of 166km. (perigee for GT.-4) the dip of the horizon is about 13° and at a height of 297 km. (apogee for GT-4) it is about 17°. Second, the auroral zone, being controlled by the geomagnetic field, is inclined to parallels of geographic latitude as illustrated en planche 15. Nighttime passes over the eastern United States or over southern Australia bring the spacecraft closest to the auroral zone. On several occasions auroras were seen in the Australia-New Zealand region. Plate 16 (Fig. 32-7 of NASA SP-121) shows a reproduction of a sketch made by the Gemini 7 crew. An auroral arch is seen below the airglow layer.

La visibilité des étoiles

Les orbites de satellites sont à une altitude minimum de 160 km environ, où le "ciel" au-dessus n'est pas le bleu familier tel qu'il est depuis la surface de la Terre. Since the small fraction of the atmosphere above the space-craft produces a very low amount of scattering, even in full sunlight, it was anticipated that the day sky from a spacecraft would therefore display the full astronomical panoply. This was decidedly notthe case. All the American astronautes have expressed themselves most forcefully that during satellite daytime, i.e., when the sun is above the horizon, they could not see the stars, even the brighter ones. Only on a few occasions, if the low sun was completely occulted by the spacecraft were some bright stars noted. L'incapacité à observer les étoiles comme anticipé est attribuée à 2 raisons :

- les surfaces de fenêtre de satellite scattered light from the oblique sun or even from the earth sufficiently to destroy the visibility of stars, just as does the scattered light of our daytime sky at the earth's surface; and

- les astronautes ne sont généralement pas bien adaptés à l'obscurité, comme mentionné dans la section 5 de ce chapitre.

Mention a déjà été faite de la dispersion dans la visibilité des étoiles durant la nuit satellitaire en raison de la souillure des fenêtres. Dans les meilleures conditions de fenêtre le ciel astronomique est rapporté être semblable à celui depuis un appareil à 40000 pieds. Under the particularly poor conditions of Mercury 8, astronaut Schirra, who is very familiar with the constellations, could not distinguish la Voie Lactée.

Météores

En général, les meteors deviennent lumineux en-dessous de 100 km, bien en-dessous de toute orbite stable. Bien que des recherches organisées de meteors trails n'aient pas fait partie des plans scientifiques des programmes de la NASA, des observations sporadiques furent faites par les astronautes qui signalérent que les traînées de meteors pouvaient être facilement distinguées de d'éclairs de foudre. Because of their sporadic nature, these observations cannot be systematically compared with the ground-observed statistics of the known variation of meteors during the year as the earth crosses the paths of inter- planetary debris. However, Gemini 5 was put into orbit shortly after the peak of the August Leonid shower and ground observations of the shower were confirmed in a rough way when astronautes Cooper and Conrad observed a significant number of meteor flashes.

The Zodiacal Light Band

Two factors tend to offset each other in the observation of the zodiacal light band from a spacecraft. A favorable factor is that the zodiacal band gets very rapidly brighter as it is observed as close as some 5° or 6° to the sun, as is possible from spacecraft in contrast with the twilight restriction on the earth's surface of about 25°. The ratio of brightness at an elongation of 5°, B(5), to that at 25°,8(25), is

| B(5)

B (25) |

= 50 |

At the same time, it is difficult to detect the zodiacal band through the spacecraft window with its restricted angular view since one can- not sweep his eyes over a wide enough arc to see the bright band standing out with respect to the darker adjacent sky. By contrast, to locate the zodiacal band observing from the earth's surface, one can sweep over an arc of some 90°, in the center of which the bright band can be readily distinguished.

The most convincing description of a visual sighting of the zodiacal band was by astronaut Cooper (Mercury 9). From his description, I concluded that he distinguished the zodiacal band some from the sun.

Twilight Bands

The satellite "day" for orbits relatively near the earth is about 45 mm. long. The sunrise and sunset sequence occurs during each satellite day. The bright twilight band extending along the earth's surface and centered above the sun is referred to by the astronautes as of spectacular beauty.

Observations d'artefacts dans l'espace

Dans la décade depuis le lancement de Sputnik I (4 Octobre 1957) un grand nombre d'objets a été mis en orbite. Avec chaque lancement, une moyenne de 5 objets partent en orbite. Au 1er Janvier 1967, un total de 2606 objets avaient été identifiés d'après 512 lancements, sur lesquels 1139 étaient toujours en orbite et 1467 étaient réentrés. Les objets en orbites quasi-stable sont catalogués par le Commandement de la Défense Aérienne Nord Americain (NORAD), et les listes mises à jour de caractéristiques orbitales sont données annuellement dans Planetary and Space Science (Quinn et King-Hele, 1967) à partir duquel les statistiques tabulaires et graphiques ont été préparées pour ce rapport (tableaux 7 et 8 et figure 6).

| Année calendaire | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | Total à ce jour | Réentrées durant l'année précèdente |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morceaux mis en orbite durant l'année calendaire | 5 | 12 | 15 | 50 | 297 | 190 | 204 | 329 | 950 | 554 | 2606 | |

| Decays as of: | ||||||||||||

| 1 Janvier 1963 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 22 | 64 | 92 | 201 | |||||

| 1 Janvier 1964 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 22 | 66 | 139 | 83 | 333 | 132 | |||

| 1 Janvier 1965 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 22 | 66 | 141 | 87 | 210 | 549 | 216 | ||

| 1 Janvier 1966 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 23 | 68 | 141 | 93 | 233 | 380 | 961 | 412 | |

| 1 Janvier 1967 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 23 | 71 | 142 | 98 | 241 | 455 | 414 | 1467 | 506 |

| Toujours en orbite au 1er Janvier 1967 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 27 | 226 | 48 | 106 | 88 | 495 | 140 | 1139 | |

| Morceaux en orbite | Decayed | Toujours en orbite (1er Janvier 1967) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Satellites Instrumentés | 643 | 379 | 264 |

| Fusées séparées | 298 | 179 | 119 |

| Autres fragments | 1665 | 909 | 756 |

| Total | 2606 | 1467 | 1139 |

| % | 100,0 | 56,3 | 43,7 |

At any given moment during the two-year period of the Gemini program (1965 and 1966) approximately 1000 known objects were in orbit. During the same biennium, there was a total of 918 known reentries. Even though the probability of a collision with an orbiting artifact is statistically trivial, NASA and NORAD coordinated closely to keep track of the relative positions in space of the objects orbiting there.

Proton III

An interesting example of an unexpected sighting of another space-craft was made by the Gemini 11 astronautes. Quoting from the transcript (GT-ll, bande 133, page 1)

We had a wingman flying wing on us going into sunset here, off to my left. A large object that was tumbling at about 1 rps and we flew -- we had him in sight, I say fairly close to us, I don't know, it could depend on how big he is and I guess he could have been anything from our ELSS* to something else. We took pictures of it.

The identification of the sighting (bande 209, page 2) was given as follows:

We have a report on the object sighted by Pete Conrad over Tananarive yesterday on the 18th revolution. It has been identified by NORAD as the Proton III satellite. Since Proton III was more than 450 kilometers from Gemini 11, it is unlikely that any photographs would show more than a point of light.

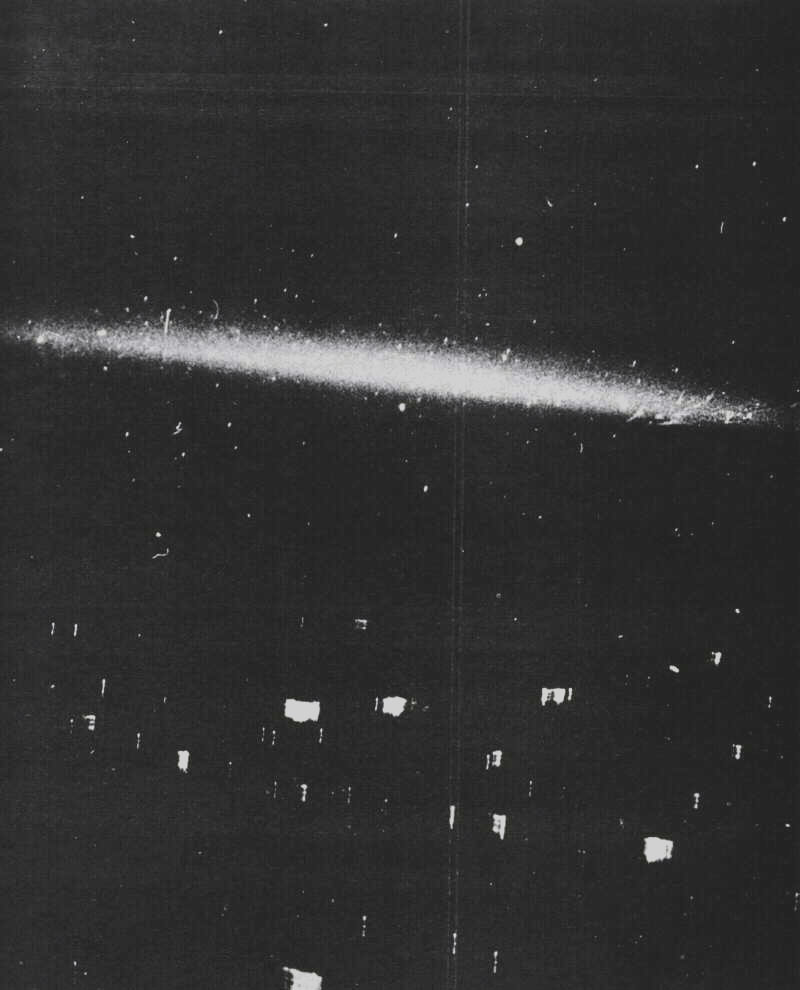

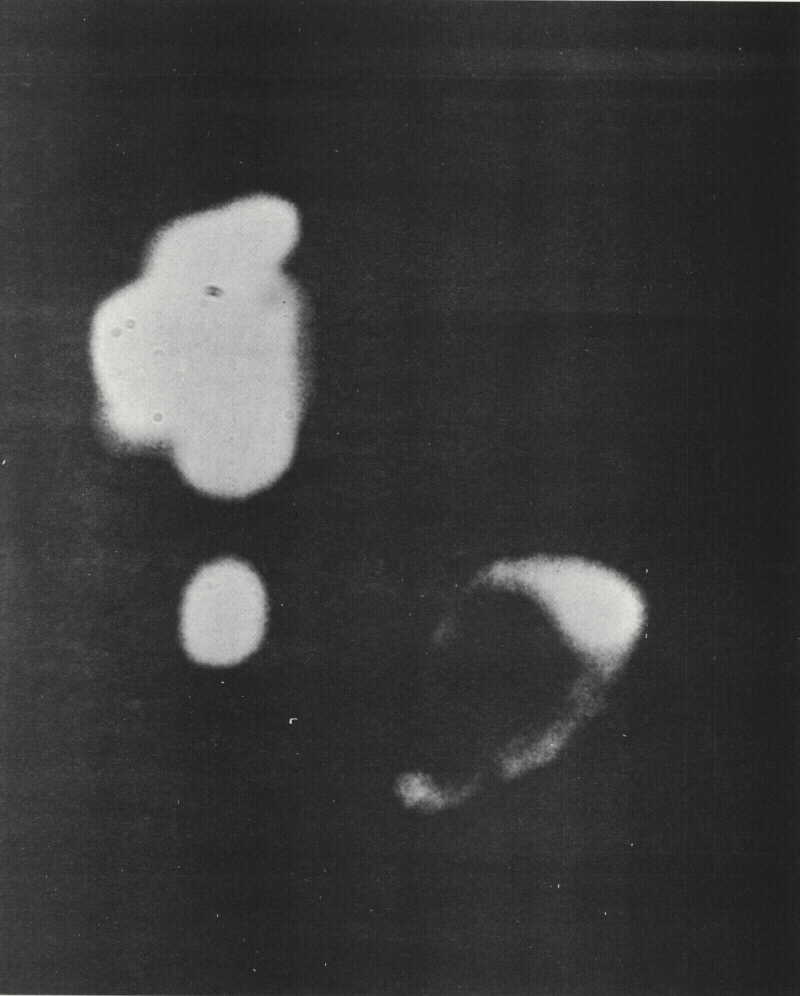

The pictures referred to are shown in enlargement in Plates 17 and 18. The Proton III satellite and its rocket are included in the P.A.S.S. listings under the numbers 1966-60A and 1966-60B with the following characteristics:

* ELSS extravehicular life support system

| Satellite | Booster | |

|---|---|---|

| 1966-60A | 1966-608 | |

| Date de lancement | 6 Juillet 1966 | 6 Juillet 1966 |

| Durée de vie | 72,20 jours | 46,33 jours |

| Date de réentrée prédite | 16 Septembre 1966 | 21 Août 1966 |

| Forme | Cylindre | Cylindre |

| Poids | 12200 kg. | 4000 kg. (?) |

| Taille | 3 m de long (?) | 4 m de diamêtre (?) |

| 10 m de long (?) | 4 m de diamêtre (?) | |

| Caractéristiques orbitales | Voir P.A.S.S. Vol.15, p. 1,192 (1967) | |

Inspection of the photos taken at the time of this sighting (Plates 17 and 18 ) reveals considerably more detail than just a point of light. If the distance from the spacecraft to Proton III is given by the NORAD calculations, then we may infer the physical separation of the several objects in the photographs. Plates l7 and 18 are 100 x enlargements of the photographs of Proton III made with the Hasselblad camera of 38 mm. focal length. The scale on the original negatives was 1 mm. = 1/38 radian = 1°.508. The scale on the enlargements is therefore 1 mm. = 0.°.01508. Four distinct objects can be distinguished with extreme separation of 30 mm. corresponding to 0°.452 or 3.55 km. at a distance of 450 km. The minimum separation of any two components is about one third of the above or more than 1 km. Referring to the table of the Proton III dimensions it is obvious that the photographs are recording multiple pieces of Proton III including possibly its booster plus two other components.

Radar Evaluation Pod

The sighting of objects associated with a Gemini mission itself is an interesting part of the record. In Gemini 5 a rendezvous exercise was performed with a Radar Evaluation Pod (REP), a package equipped with flashing lights and ejected from the spacecraft early in the mission. Although the primary aim of the rendezvous exercise was to test radar techniques, the Gemini astronautes, in their conversations with NASA control , commented (Table 9) on the visibility or non-visibility of the REP. Plate 19 shows a photograph of the REP made by the astronautes

Referring to Fig. 4 , Section 4 of this chapter, the REP illuminated by sunlight should be of apparent magnitude -2 at a distance of 10 km. (assuming a 1 meter effective diameter) and magnitude +3 at a distance of 100 km.

The Agena Rendezvous

The rendezvous with the REP was a rehearsal for the rendezvous and docking exercises with the Agena. In turn the Agena exercises were rehearsals for the coming Apollo program in which space dockings will be a part of both the terrestrial and lunar flights.

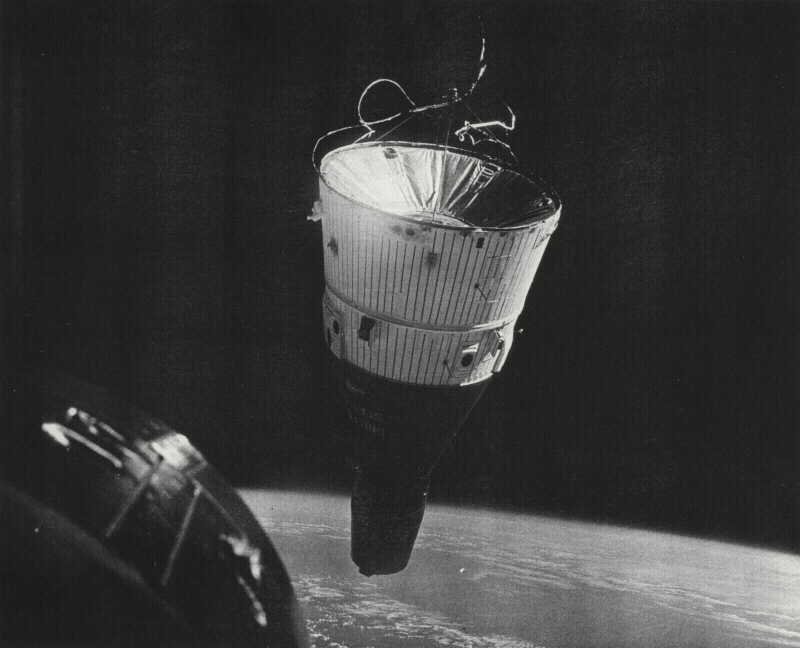

The Agena vehicle is a cylindrical object 8 m. long with a diameter of 1.5 in. Its size makes it a conspicuous object at considerable distances when illuminated by the sun. Plate 20 illustrates its appearance at distances varying between 25 and 250 ft. At 250 ft. its apparent magnitude when sun-illuminated is -9.74 (about 1/13 the brightness of the full moon)

The original plan was to rendezvous with an Agena on the Gemini missions 6-12 inclusive. The planned procedure was to send up the Agena prior to the launching of the manned spacecraft. In the case of the GT-6, the associated Agena did not achieve orbit, so a rendezvous with GT-7 was substituted.

| Bande | Page | Commentaire |

|---|---|---|

| 40 | 1 | REP about 1 mile away |

| 60 | 1, 3 | REP near spacecraft (~4000 ft.) and is visible (flashing light) |

| 62 | 1, 23 | |

| 67 | 3, 4 | Looked for REP -- Could not sec |

| 68 | 1 | Looked for REP -- Could not see |

| 76 | 1 | Looked for REP -- Could not see |

| 80 | 2 | Looked for REP at distance of 75 mi. Did not see. |

| 234 | 2, 3 | Discussion of photography of REP |

The sun-illuminated Agena, when close to the astronautes, was of blinding brightness. Details could be made out at a distance of 26 km (GT-11, tape 216, page 2). It was picked up visually at distances up to 122 km (GT-11, tape 50, page 7). Assuming an effective diameter of 4.0 meters, we note from equation (1) that its apparent magnitude was about +0.3 at a distance of 122 km.

The Rendezvous of GT-6 and GT-7

The rendezvous of these two spacecraft involved close coordinations of radar and visual acquisitions and of ground and on-board calculations. Some of the most spectacular photographs of the entire Mercury-Gemini program were obtained during the rendezvous and one is included in this report (planche 21).

Some of the drama of the rendezvous which also suggests the nature of the visual sightings is brought out in the words

of astronaut Lovell during the post-flight press conference (tape 5, page 1). The question was asked of both

astronautes - "What was your first reaction when you realized you had successfully carried off rendezvous?"

Answer (Lovell):

I can only talk for myself, looking at it from a passive point of view. I think Frank (Borman) and I expressed the same feeling -- it was night time just become light, we were face down and, coming out of the murky blackness of the dark clouds this little point of light. The sun was just coming up and it was not illuminating the ground yet, but on the adapter of 6 (Gemini 6) we could see this illumination. As it got closer and closer, it became a half moon and, it was just like it was on rails. At about half a mile, we could see the thrusters firing like light hazes; some thing like a water hose coming out -- just in front of us without moving it stopped, fantastic.

The Glenn "Fireflies", Local Debris

During the first Mercury manned orbital space flight, astronaut Glenn reported as follows:

The biggest surprise of the flight occurred at dawn. Coming out of the night on the first orbit, at the first glint of sunlight on the spacecraft, I was looking inside the spacecraft checking instruments for perhaps 15 to 20 seconds. When I glanced back through the window my initial reaction was that the spacecraft had tumbled and that I could see nothing but stars through the window. I realized, however, that I was still in the normal attitude. The spacecraft was surrounded by luminous particles.

These particles were a light yellowish green color. It was as if the spacecraft were moving through a field of fireflies. They were about the brightness of a first magnitude star and appeared to vary in size from a pin-head up to possibly 3/8 inch. They were about 8 to 10 feet apart and evenly distributed through the space around the spacecraft. Occasionally, one or two of them would move slowly up around the spacecraft and across the window, drifting very, very slowly, and would then gradually move off, back in the direction I was looking. I observed these luminous objects for approximately 4 minutes each time the sun came up.

During the third sunrise I turned the space-craft around and faced forward to see if I could determine where the particles were coming from. Facing forwards I could see only about 10 percent as many particles as I had when my back was to the sun. Still, they seemed to be coming towards me from some distance so that they appeared not to be coming from the spacecraft.

Dr. John A. O' Keefe has concluded that "the most probable explanation of the Glenn effect is millimeter-size

flakes of material liberated at or near sunrise by the spacecraft"

(NASA, 196 , pp. l99-203).

Reference is here made to Fig. 5, Section 4. We note that the apparent magnitude of the sun-illuminated sphere of diameter 1 mm. at 1 m. is -7. This is in general agreement with the description of brightness given by Glenn who referred to them as looking like steady fireflies.

Observations by astronautes in subsequent flights showed that O'Keefe's interpretation is almost certainly correct. Astronaut Carpenter in Mercury 7 found for example that (NASA SP-6, p. 72).

At dawn on the third orbit as I reached for the densitometer, I inadvertently hit the spacecraft hatch and a cloud of particles flew by the window . . . I continued to knock on the hatch and on other portions of the spacecraft walls, and each time a cloud of particles came past the window. The particles varied in size, brightness, and color. Some were grey and others were white. The largest were 4 à 5 fois la taille des plus petits. One that I saw was a half inch long. It was shaped like a curlicue and looked like a lathe turning.

A modification of the "knocking" technique used by astronaut Carpenter to get the "firefly" effect was used by some of the Gemini astronautes who discovered that a brilliant display resulted from a urine dump at sunrise. The crystals which formed near the spacecraft, when illuminated by the sun, looked like brilliant stars. Plate 22 illustrates the effect (GT-6, Magazine B, Frame 29).

Similar spectacular effects were obtained by venting one of the on-board storage tanks when the sun was low. One such event is described by astronaut Conrad (GT-5, tape 269, page 2) speaking to the ground crew:

We just had one of our more spectacular sights of our flight coming into sunset just before you acquired us. Either our cryo-hydrogen or our cryo-oxygen tank vented, and it just all froze when it came out and it looked like we had 7 billion stars passing by the windows which was really quite a sight.

The Glenn particles were observed to move with respect to the spacecraft at velocities of 1 to 2 m/sec. Thus the particles and the spacecraft have velocities identical within about 1 part in 4000 in all three coordinates. According to O'Keefe this implies that the orbital inclinations were the same within �0.01�.

The Rocket Boosters

The rocket booster often achieves orbit along with the primary spacecraft, and can often be seen by the astronautes until the relative orbits have diverged to put the booster out of sight.

Extra-Vehicular Activity Discards

Because of the crowded conditions in the Gemini spacecraft, the usual procedure after completion of extra-vehicular activity (EVA) was to discard all the equipment and material that had been essential to the EVA but was now useless. This material stayed in essentially the same orbit as the spacecraft and was visible to the astronautes after the disposal. An interesting example occurred in Gemini 12 mission when four discarded objects were seen some time later as four "stars" (GT-12., Astronaut debriefing, page K/3, 4).

Lovell:

I did not see any objects in space other than the ones we had put there except for several meteors that whistled in below us during the night passes. I might mention we -- during the last standup EVA we discarded, in addition to the ELSS, three bags, one of which was the umbilical bag and the other had some food in it and the third one had several hoses that we were discarding. And I pushed these forward with a velocity, I would guess, might be 3 or 4 feet per second. And we watched these for quite some time period until they finally disappeared about 2 maybe 3 or possibly 4 orbits later at sunrise condition, we looked out again and saw 4 objects lined up in a row and they weren't stars I know. They must have been these same things we tossed overboard.

Much has been made of this event by John A. Keel, who apparently thought there was discrepancy between the number of objects thrown out by the astronautes (three) and the number of objects later seen as illuminated objects (four). The pertinent part of Keel's article follows (Keel, 1967):

You never read about it in your local newspaper but during the last successful manned space shot -- the flight of Gemini 12 in November 1966 -- astronautes James Lovell and Edwin Aldrin reported seeing four unidentifiable objects near their orbit.

"We saw four objects lined up in a row" Captain Lovell told a press conference on November 23rd, "and they weren't stars I know". Several orbits earlier, he explained, they had thrown three small plastic bags of garbage out of the spacecraft. He hinted that these four starlike objects standing in a neat row were, some how, that trio of non-luminous garbage bags.

A careful reading of the original transcript however shows that four objects were discarded, i.e. the ELSS, plus three bags.

Objets volants Non Identifiés

Il y a 3 observations visuelles faites par des astronautes en orbite qui, du jugement de l'auteur, n'ont pas été expliquées de manière adéquate. Il s'agit de :

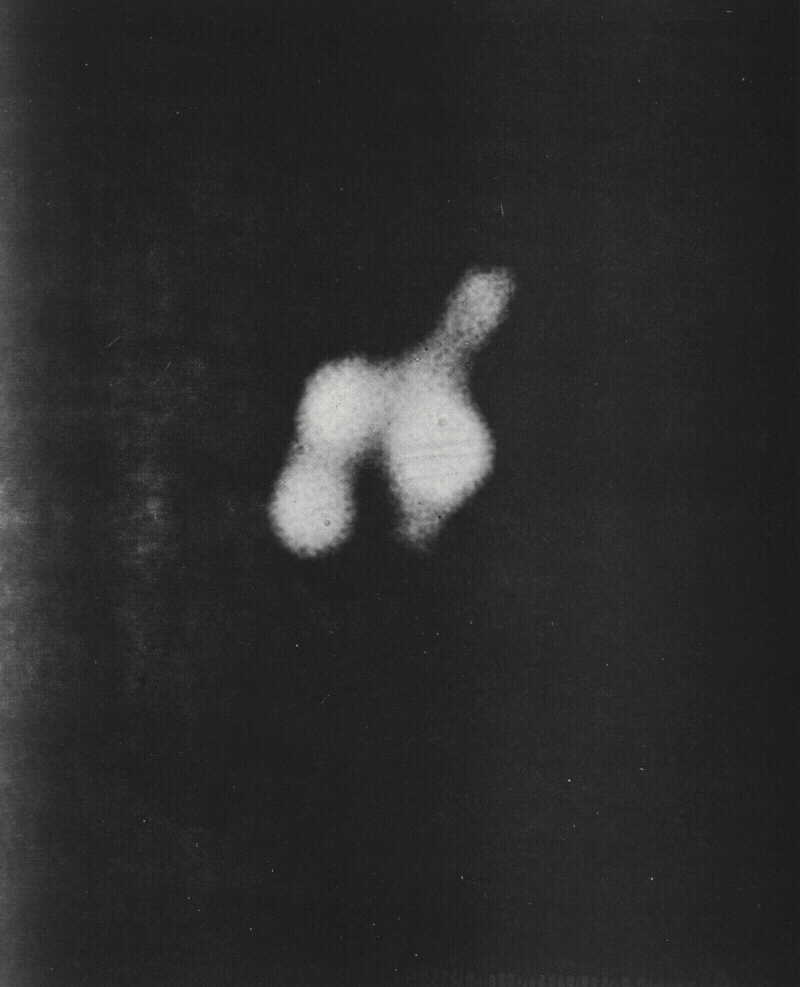

- Gemini 4, astronaute McDivitt. Observation d'un objet cylindrique avec une protubérance.

- Gemini 4, astronaute McDivitt. Observation d'une lumière brillante en déplacement à un niveau plus élevé que celui du vaisseau spatial Gemini.

- Gemini 7, astronaute Borman vit ce qu'il désigna être un "bogey" volant en formation avec le vaisseau spatial.

Gemini 4, objet cylindrique avec protubérance

L'astronaute McDivitt décrivit voir à 3 h 00 (CST) le 4 Juin 1965 un objet cylindrique qui semblait avoir des bras en sortant, une description suggérant un vaisseau spatial avec une antenne.

J'ai eu une conversation avec l'astronaute McDivitt le 3 Octobre 1967, au sujet de cette observation et reproduit ici ma synthèse de la conversation.

McDivitt saw a cylindrical-shaped object with an antenna-like

extension. The appearance was something like the second phase of a Titan (not necessarily implying that that is

actually what be saw) It was not possible to estimate its distance but it did have angular extension, that is it did

not appear as a "point

." It gave a white or silvery appearance as seen against the day sky. The spacecraft was

in free drifting flight somewhere over the Pacific Ocean. One still picture was taken plus some movie exposures on

black and white film. The impression was not that the object was moving parallel with the spacecraft but rather that

it was closing in and that it was nearby. The reaction of the astronaut was that it might be necessary to take action

to avoid a collision. The object was lost to view when the sun shone on the window (which was rather dirty). He tried

to get the object back into view by maneuvering so the sun was not on the window but was not able to pick it up again.

When they landed , the film was sent from the carrier to land and was not seen again by McDivitt for four days. The NASA photo interpreter had released three or four pictures but McDivitt says that the pictures released were definitely not of the

object he had seen. His personal inspection of the film later revealed what he bad seen although the quality of the

image and of the blown-up point was such that the object was seen only "hazily

" against the sky. But he feels

that a positive identification had been made.

It is McDivitt's opinion that the object was probably some unmanned satellite. NORAD made an investigation of possible satellites and came up with the suggestion that the object might have been Pegasus which was 1200 miles away at the time. McDivitt questions this identification.

The NORAD computer facility's determination of the distances from GT-4 to other known objects in space at the time of the astronaut McDivitt sighting yielded the following tabulation.

| Objet | Nombre | Heure (CST) | Distance en km. depuis GT-4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spodats (NORAD) | International (PASS) | |||

| Fragment | 975 | 2:56 | 439 | |

| Tank | 932 | 3:01 | 740 | |

| Fragment | 514 | 3:04 | 427 | |

| Omicron | 646 | 3:06 | 905 | |

| Omicron | 477 | 3:07 | 979 | |

| Fragment | 726 | 3:09 | 625 | |

| Fragment | 874 | 3:13 | 905 | |

| Omicron | 124 | 3:13 | 722 | |

| Pegasus Debris | 1385 | 3:16 | 757 | |

| Yo-Yo Despin Weight | 167 | 3:18 | 684 | |

| Pegasus B | 1965-39A | 3:06 | 2000 | |

A preliminary identification of the object as Pegasus B is suspect. When fully extended Pegasus B has a maximum

dimension of 29.3 meters, which corresponds to 1/20 minute of arc at a distance of 2000 km. This is much too small an

angular extension for the structure of the craft to be resolved and thus does not agree with the description of "arms

sticking out

." Later in the mission Pegasus B was at a much more favorable distance (497 km.) from the Gemini 4

spacecraft or four times as close as during, the reported sighting. astronautes McDivitt and White reported that they were not successful in a serious attempt to

visually identify the Pegasus B satellite during this encounter.

The ten objects in addition to Pegasus B in the NORAD list were all at considerably greater distances away from GT-4 than an admittedly crude estimate of 10 miles (16 km.) made by McDivitt, and were of the same or smaller size than Pegasus B. They would not appear to be likely candidates for the object sighted by the astronaut.

Gemini 4, moving bright light, higher than spacecraft

At 50h 58m 03s of elapsed time of GT-4, astronaut McDivitt made the following report.

Just saw a satellite, very high . . . spotted away just like a star on the ground when you see one go by, a long, long ways away. When I saw this satellite go by we were pointed just about directly overhead. It looked like it was going from left to right . . . back toward the west, so it must have been going from south to north.

Although McDivitt referred to this sighting as a satellite, I have included it among the puzzlers because it was higher than the GT-4 and moving in a polar orbit. It was reported as looking like a "star" so we have no indication of an angular extension.

The suggestion at the time of sighting that this was a satellite has not been confirmed, so far as I know, by a definite identification of a known satellite.

Conversations with McDivitt indicate that, on one other occasion, off the coast of China, he saw a "light" that was moving with respect to the star background. No details could be made out by him.

Gemini 7, "bogey"

Des portions de la transcription (CT 7/6, bande 51, pages 4, 5, 6) de Gemini 7 sont reproduites ici. La conversation qui suit eut lieu entre le vaisseau spatial et le contrôle au sol à Houston et se réfèrent à une observation au début de la 2ᵉ révolution du vol :

Vaisseau spatial : Gemini 7 ici, Houston nous recevez-vous ?

Capcom : Fort et clair. 7, allez-y.

Vaisseau spatial : Bogey à 10 heures en haut.

Capcom : Ici Houston. Répétez 7.

Vaisseau spatial : Dit que nous avons un bogey à 10 heures en haut.

Capcom : Roger. Gemini 7, est-ce le booster ou est-ce une véritable observation ?

Vaisseau spatial : Nous avons plusieurs, looks like debris up here. Véritable observation.

Capcom : Vous avez plus d'informations ? Estimation de distance ou taille ?

Vaisseau spatial : Nous avons aussi le booster en vue.

Capcom : Compris que vous avez le booster en vue, Roger.

Vaisseau spatial : Ouais, nous avons a very, very many -- look like hundreds of little particles

banked on the left out about 3 to 7 miles.

Capcom : Understand you have many small particles going by on the left. At what distance?

Vaisseau spatial : Oh about -- it looks like a path of the vehicle at 90 degrees.

Capcom : Roger, understand that they are about 3 to 4 miles away.

Vaisseau spatial : They are passed now they are in polar orbit.

Capcom : Roger, understand they were about 3 or 4 miles away.

Vaisseau spatial : That's what it appeared like. That's roger.

Capcom : Were these particles in addition to the booster and the bogey at 10 o'clock high?

Vaisseau spatial : Roger -- Spacecraft (Lovell) I have the booster on my side, it's a

brilliant body in the sun, against a black background with trillions of particles on it.

Capcom : Roger. What direction is it from you?

Vaisseau spatial : It's about at my 2 o'clock position. (Lovell)

Capcom : Does that mean that it's ahead of you?

Vaisseau spatial : It's ahead of us at 2 o'clock, slowly tumbling.

The general reconstruction of the sighting based on the above conversation is that in addition to the booster travelling in an orbit similar to that of the spacecraft there was another bright object (bogey) together with many illuminated particles. It might be conjectured that the bogey and particles were fragments from the launching of Gemini 7, but this is impossible if they were travelling in a polar orbit as they appeared to the astronautes to be doing.

Résumé et évaluation

Many of the engineering problems involved in putting men into orbit would have been alleviated if it had been decided to omit the windows in the spacecraft, although it is questionable whether the astronautes would have accepted assignments in such a vehicle. The windows did make possible many planned experiments but the observations discussed in this chapter are largely sporadic and unplanned. The program of engineering, medical and scientific experiments was sufficiently heavy to keep the astronautes moderately busy on a regular working schedule but left reasonable opportunity for the inspection of natural phenomena.

The training and perspicacity of the astronautes put their reports of sightings in the highest category of credibility. They are always meticulous in describing the "facts," avoiding any tendentious "interpretations." The negative factors inherent in spacecraft observations which have been mentioned in this chapter would seem to be more or less balanced by the positive advantages of good observers in a favorable region.

Les 3 observations inexpliquées qui ont été glanées d'une grande masse de rapports sont un défi pour l'analyste. Particulièrement intriguant est la 1ʳᵉ sur la liste, l'observation de jour d'un objet montrant des détails tels que des bras (antennes ?) protubérant d'un corps ayant une extendue angulaire notable. Si la liste du NORAD des objets près du vaisseau spatail GT-4 au moment de l'observation est complète comme on peut le prèsumer, nous devrons trouver une explication rationnelle ou, alternativement, la garder sur notre liste des non-identifiés.

- Air Force Cambridge Research Center, The U.S. Extension to the ICAG Standard Atmosphere, 1958.

- Duntley, Seibert Q., Roswell W. Austin, J. H. Taylor, et J. L. Harris. "Visual acuity and astronaut visibility, NASA SP-138, (1967)

- Hymen, A. "Utilizing the human environment in space," Human Factors, vol. 5, n° 3, (1963-06-03).

- Jacchia, L. G. Philosophical Transactions, Royal Society, London A262 (1967), 157.

- King-Nele, D.G. Theory of Satellite Orbits in an Atmosphere ,London: Butterworths, 1964.

- McCue, G. A., J. G. Williams, H. J. Der Prie & R. C. Hoy. North American Aviation Report, n° S 10 65-1176, 1965.

- NASA Reports on Mercury and Gemini Flights as follows:

- Results of the First United States Manned Orbital Space Flight (1962-02-20). Transcript of Air-Ground Communications of the MA-6 flight is included.

- NASA SP-6. Results of the Second United States Manned Orbital Space Flight (1962-05-24). Transcript of the Air-Ground Voice Communications of this MA-7 flight is included.

- NASA SP-12. Results of the Third United States Manned Orbital Space Flight (1962-10-03). Transcript of the Air-Ground Communications of this MA-8 flight is included.

- NASA SR-45. Mercury Project Summary including results of the Fourth Manned Orbital Flight (15-16 May 1963). Includes a transcript of Air-Ground Voice Communication for MA-9.

- MA-9 Scientific Debriefing held on (1963-06-02).

- Manned Space Flight Experiments Symposium, Gemini Missions III and IV, (18/1965-10-19).

- NASA SP-121, Gemini Mid Program Conference, (February 1966). NASA SP-138, Gemini Summary Conference, (1967-02).